Alex Jones, Cool Trust, and Arbiters of Truth

The law and the courts are now on the front lines of the information battlefield...and that should make us worry.

Conspiracy theorist Alex Jones filed for bankruptcy on Friday, after being ordered to pay over $1.5 billion to several parents of victims of the 2012 Sandy Hook shooting in Connecticut who had sued him for defamation. On his radio program and website, Jones had repeatedly accused the parents of being “crisis actors” who were lying about their children dying and claimed the entire event was a “false flag” operation. The lawsuits and the awards demonstrate that the court system may be the only institution left that can adequately police the line between truth and lies — which is not a good sign for our democracy.

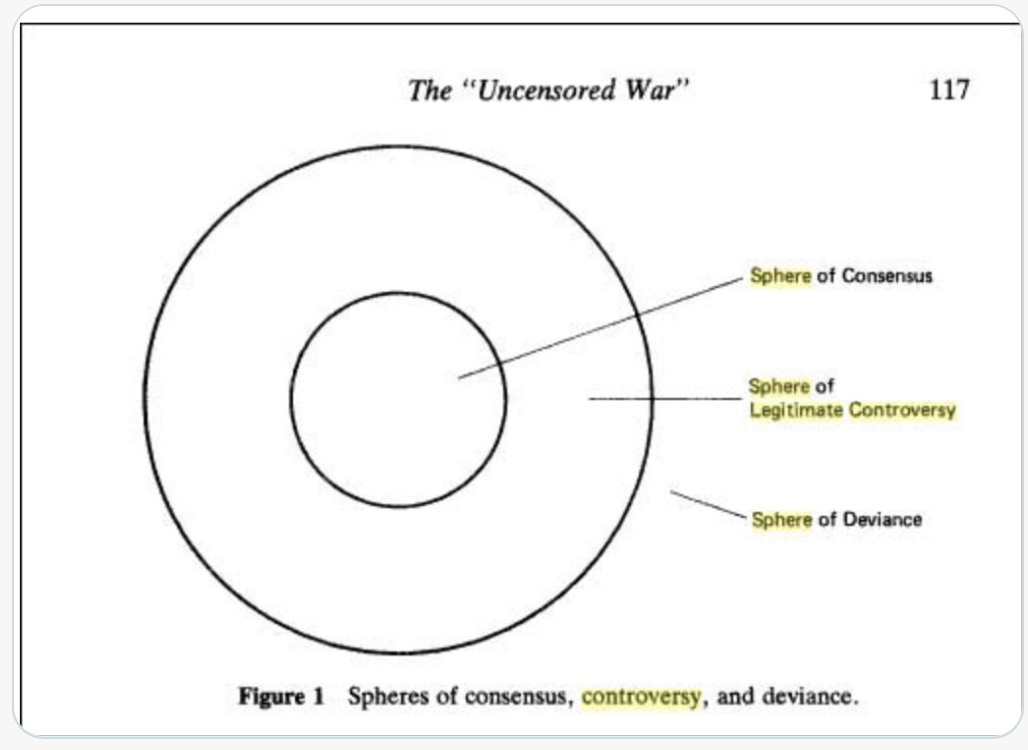

I’ve been thinking about this ever since I read a Twitter thread by NYU professor Jay Rosen, who posted the following diagram (created by media scholar and UCSD Professor David C. Hallin):

Basically, the diagram shows three spheres: the sphere of consensus (things on which all reasonable people agree and that are beyond debate); the sphere of legitimate controversy (ideas among which reasonable people can disagree and can be debated); and the sphere of deviance (positions that are unworthy of debate, or as Rosen has written, have been defined as “unacceptable, radical, or just plain impossible”).

As Rosen has observed, traditionally journalists have defined and guarded the boundaries of these spheres — they were the gatekeepers of what was newsworthy, what deserved “two sides” coverage, and what was not given a platform. He notes that journalists were able to maintain this role because viewers and readers were, as he calls them, “atomized” — that is, disconnected from each other and vertically connected to sources of information. I will add to that the time when these delineations existed most rigidly was when there were few news sources (remember when there were only three major news networks?).

The emergence of the internet and social media, Rosen argues, erases this atomization, allowing views and readers to connect horizontally — which means that these spheres are no longer determined by journalists. Since people can share information among and with each other, they can redefine what can enter into the spheres of consensus and legitimate controversy.

This, of course, has benefits. Consider, for example, Black Lives Matter, which brought attention to a pervasive pattern of police brutality against Black Americans. The ability to share videos across social media platforms shined a spotlight on a side of America that had largely been excluded by traditional media and of which many Americans were unaware. The same could be said for the #MeToo movement, which allowed victims of sexual harassment and misconduct to connect with each other and bring to light an issue which had, in some instances, been deliberately barred from coverage by major news networks. In other words, things that may have been (wrongly) relegated to the “sphere of deviance” in the traditional model have found a place in today’s information space, democratizing the voices that can be heard and bringing these issues into the sphere of controversy, if not consensus.

As Rosen notes in his thread, however, there is a dark side to this horizontal connection. There are now no gatekeepers at all, so the divisions between the three spheres aren’t just blurred, they basically don’t exist. Just look at the last week — it’s 2022 and Kanye West has a platform to profess his admiration for Hitler (incidentally, on Alex Jones’ show). What was once squarely in the sphere of deviance has (apparently) become a topic of debate. From the other direction, concepts that were unquestioned — like basic science and epidemiology — are now challenged or dismissed entirely. If I had to draw a diagram of where we are today, it would be just one big sphere of controversy.

Which is where Alex Jones comes in. Jones helped spread the Pizzagate theory — this was the rumor that Hillary Clinton was running a child sex trafficking ring in the basement of a D.C. pizza parlor that resulted in a person shooting up that establishment — and, more recently, the “Stop the Steal” disinformation campaign which culminated in an attack on the U.S. Capitol. He has not only mainstreamed ideas that would have once been squarely in the sphere of deviance and brought them into the sphere of controversy, but he profits from it. The only gatekeepers who might restrain him are social media platforms if they choose to self police. Even then, their efforts might slow down the spread of his conspiracy theories, but wouldn’t stop the millions readers who visit his website each month from consuming his “news” directly.

Enter the courts. The judicial system is one of the few (only?) institutions left where truth actually matters, and can be enforced. We saw this most clearly in the dozens of lawsuits Trump and his allies filed after the 2020 election alleging widespread voter fraud — sixty three cases were dismissed, manly for lack of proof. This is because in court, we have rules about truth. Facts have to exist in order to be presented as evidence. Judges determine what issues are in dispute, and what is irrelevant. Juries can’t make up their own evidence; they have to weigh and evaluate what is presented to them. In fact, the only defense to defamation is to demonstrate that what you have said is true — and even Jones had to admit on the witness stand that Sandy Hook was real.

These are welcome outcomes, but leaving courts to arbitrate what is true and what is not is not a great development overall. For one thing, most of the disinformation narratives we must contend with won’t end up being litigated, leaving them to cause chaos and harm, as Jones has. More importantly, an increase in litigation is a symptom of deterioration of social trust. Robert Putnam (whose work we will be reading in my Substack class, Democracy in the (Dis)Information Age) notes that when a society has a high level of generalized trust — basically, when we follow the Golden Rule and act in ways that benefit our collective self interest, like behaving honestly — it is healthier and more efficient. That’s because we can count on others to uphold their social and civic obligations to us, and we do the same (he calls this “generalized reciprocity” or “thin trust”). As he writes:

A society that relies on generalized reciprocity is more efficient than a distrustful society, for the same reason that money is more efficient than barter. Trust lubricates social life. Networks of civic engagement also facilitate coordination and communication and amplify information about the trustworthiness of other individuals.

When that generalized trust breaks down, it is replaced by “cool trust” — formal rules and enforcement mechanisms that force people to uphold their civic and social obligations to society. Putnam continues:

[O]ne alternative to generalized reciprocity and socially embedded honesty is the rule of law — formal contracts, courts, litigation, adjudication, and enforcement by the state. Thus, if the lubricant of thin trust is evaporating from society, we might expect to find a greater reliance on the law as a basis of cooperation. If the handshake is no longer binding and reassuring, perhaps the notarized contract, the deposition, and the subpoena will work almost as well.

Having courts police our basic obligations to each other — like telling the truth about actual events — isn’t sustainable for a healthy democracy. We need to have mechanisms outside the judicial system to resurrect some boundaries between agreed upon facts, legitimate controversies, and ideas that are not worthy of debate. Until we can recalibrate those three spheres, perhaps the only people who will make out ahead are the lawyers.

The distinction between thin trust and cool trust is resonating with me because of work issues I've been thinking about lately, but of course they are broadly societal issues (and probably this is the reason why they are work issues). The analogy to economic practice is useful too. In "Debt: The Frist 5,000 Years" the late anthropologist David Graeber shows that during the Middle Ages, Islam had trading markets that were remarkably free of government interference because they were based on the underlying principle of mutual aid. When Adam Smith cribbed Islamic writings on economics (down to a near verbatim quote of the pin factory analogy), he kept the free market part, but replaced "mutual aid" with "competition." I'm sure I'm painting with too broad brush, but I sometimes feel that this is perhaps where trust begins to tilt from thin to cool in the West. (I know, it's much more complicated, but dang...). In any case, the cultivation of empathy and the reaffirmation of mutual aid as social foundations is a culture-wide project that we desperately need to undertake.

"If I had to draw a diagram of where we are today, it would be just one big sphere of controversy" and that is as concise a statement of where we are as any that I've read. I am enjoying your Freedom Academy pieces. Thanks!