Discover more from The Freedom Academy with Asha Rangappa

Anatomy of a (Mass) Murder

Why our gun laws, media ecosystem, and political climate are a ticking time bomb for right-wing extremist violence, both figuratively and literally.

At 9 a.m. on April 19, 1995, I was in my dorm at Princeton University. Our room, 221 Cuyler Hall, was a typical Princeton quad — two small rooms with a bunk bed in each, attached to a larger common area, which is where my roommates and I were hanging out because we didn’t have classes until later that day. I remember that morning because the phone rang: It was my roommate’s mom, calling from her hometown of Shawnee, Oklahoma. She told us to turn on the TV because there had been an explosion in Oklahoma City. My roommate hung up the phone and turned on the small television set in the corner of the common room. We spent the rest of the morning in shock, watching the chaos unfold.

I’ll admit that I don’t recall much else about the Oklahoma City bombing, except that they caught Timothy McVeigh a short time later. This was well before the instantaneous availability of news on social media and still mostly in the early phase of the 24/7 news cycle (CNN existed, but Fox News didn’t). In any event, my roommates and I didn’t spend a lot of time in those last weeks of our junior year watching much TV (except once a week for Friends) so I didn’t follow all of the twists and turns of the case. And although Oklahoma City was the worst terrorist attack on U.S. soil since Pearl Harbor to that date, it really was just the beginning of a series of national tragedies that would begin to hijack the news cycle and our collective consciousness: By the time McVeigh was finally executed in June 2001, our attention and shock had been diverted and eclipsed by the 1999 high school shooting in Columbine — and 9/11 happened just three months after McVeigh was put to death, leaving domestic terrorism squarely in the rearview mirror. For these reasons, my overall recollection of Oklahoma City over the last couple of decades was really just the bare contours of the plot: McVeigh was an anti-government extremist who bombed the federal building to make his point. He was the classic “lone wolf” terrorist.

Filling in the factual gaps of my skeletal knowledge of the terrorist attack was one of the reasons it was worthwhile to read Jeffrey Toobin’s Homegrown: Timothy McVeigh and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism. But more important was the thru-line he draws from OKC to January 6, challenging the simplistic “lone wolf” narrative that has ossified around McVeigh, as it has with so many right-wing terror attacks since then. To be sure, Toobin makes clear that despite the various conspiracy theories surrounding the Oklahoma City bombing — including a concerted effort by conservative media to link it to Islamic terrorism — McVeigh acted alone (with some planning and procurement assistance from his bumbling sidekick, Terry Nichols). But the book brings to the fore all of the different forces — societal, legal, and political — which facilitated McVeigh from the beginning of his journey until the end.

What is frightening is that all of those forces exist today — some with even greater potency. Understanding how these threads came together in Oklahoma City offers a chilling picture of how imminently the domestic extremist threat looms now.

Extremism in the Military

One of the surprising things I learned from Toobin’s account is that McVeigh was a model soldier. It seems odd that someone who was so vehemently anti-federal government would shine in an environment where he is taking orders from…the federal government. But Toobin notes that the military offered McVeigh, a gun nut (more on that below), the chance to “indulge his passion for weaponry.” He also went in pre-wired with a racist worldview. The military just hardened them, as Toobin notes:

Ft. Riley was polarized along racial lines. Anti-white and anti-Black Graffiti marred many walls. The racism that McVeigh began to express during his security guard days in Buffalo deepened in the Army…. McVeigh wrote Hodge from Ft. Riley, “I used to call people ‘black’ because I only saw one side of the story. Now you can guess what I call them.” Fellow soldiers later reported to the FBI that McVeigh was fond of the n-word and referred to Black children as “nig-lets.” In the Army, McVeigh thought he was a victim of affirmative action; when two African Americans were chosen over him to attend sniper school, McVeigh was outraged because he thought he was better qualified.

Toobin concludes that “the Army enhanced and accelerated the process of radicalization” for McVeigh and others, like the members of the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys.

The link between the military service and right-wing extremism is not new: In her book, Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America, Professor Kathleen Belew traces the roots of the modern domestic extremism movement to the return of veterans from Vietnam in the 1970s, which brought life to new white power organizations even as the KKK was fading in significance and reach. (The Oath Keepers specifically recruit former military, police, and first responders — the name refers to the oath these individuals take as public servants to protect the Constitution.) Toobin states that about 15% of participants arrested for participating in the January 6 attack on the capitol are veterans or active-duty military. Recent reports on these defendants include active duty Marines, a former Navy veteran, and one person who re-enlisted in the Army after playing a role in January 6.

President Biden’s 2021 National Strategy for Countering Domestic Extremism recognized the role of government and military service in fostering extremism, promising to revise questions asked on government background check and military screening questionnaires, and stating that the Defense Department would be “reviewing and updating its definition of prohibited extremist activities among uniformed military personnel, and will consider appropriate policy recommendations and options to address such activity by and among civilian employees and contractors.”

Unfortunately, these goals have not only not been realized in practice, it appears that they have been abandoned. Just last week CNN reported that the Pentagon’s Countering Extremist Activity Working Group, created to implement measures designed to detect and weed out extremism in the military, has largely become defunct after major pushback from Republicans, and attacks from Tucker Carlson, for being too “woke.” According to the reporting, 30 Republican House members signed a letter stating that the real problem in the military was “creeping left-wing extremism.”

That came on the heels of Senator Tommy Tuberville complaining on a radio show about the Biden administration’s attempt to get white nationalists out of the military. When asked by the host whether he believed white nationalists should be in the military, Tuberville responded, “Well, they call them that. I call them Americans.”

The Stolen Gun Pipeline

The second big theme that jumped out to me in Toobin’s chronicle was how McVeigh was able to finance his operation. A big chunk of the money came from a robbery of Roger Moore, a wealthy ammunitions dealer whom McVeigh met during his rounds at various gun shows. Moore had a gun collection, Toobin recounts, which McVeigh eyed during a visit to his ranch. Later, McVeigh’s accomplice, Terry Nichols, executed a robbery at the ranch, stealing 76 guns, including handguns, long guns, and rifles. McVeigh recruited a friend named Mike Fortier to help him sell the guns at gun shows — more on that below.

The Moore robbery brought to mind a law review commentary I wrote ten years ago on the problems of personal arsenals (I think 76 guns counts as an arsenal) and how they disproportionately contribute to gun violence. In that piece I quote a statistic that 232,400 firearms are stolen each year. (My argument was that Congress should make it more expensive to build personal arsenals by levying an incremental excise tax on each gun purchase after the first.)

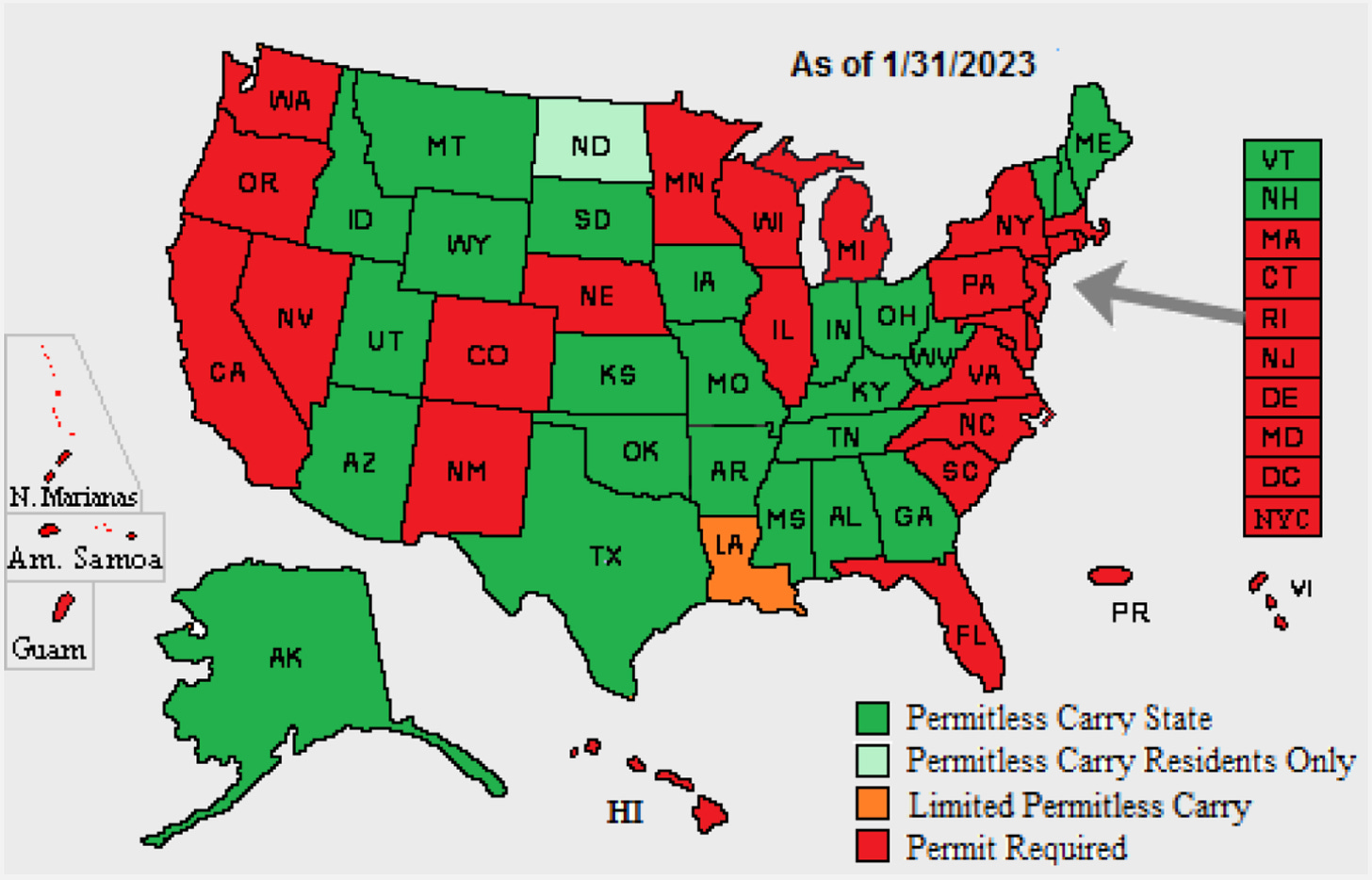

The Gifford’s Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence reveals that the number of firearms stolen from private gun owners has since jumped to 380,000 guns stolen annually, accounting for 95% of all stolen firearms. (The remaining 5% come from licensed gun dealers and interstate thefts.) A recent report from the ATF tracing guns used in crimes estimates that from 2017-2021, more than 1 million firearms were reported stolen from lawful gun owners. Here’s the catch: Most states don’t require reporting of stolen firearms, which means that the number is probably higher than that. Under federal law, only federally licensed firearms dealers are required to report stolen firearms. And the Gifford’s Center notes that only eleven states and D.C. require the reporting of any firearm, regardless of type. (Maryland and Michigan have some limited reporting requirements, and the remaining states have none — you can check out state-by-state requirements here.)

Why do we care about stolen firearms? The main reason is that they end up in the hands of people ineligible to own them and are disproportionately used in crimes. A Justice Department study, for example, found that in K-12 school shootings, 80% of perpetrators stole guns from family members. Stolen guns are also trafficked along the so-called “Iron Pipeline” into states with strong gun laws. You know how politicians love to point to the crime problem in New York? Consider this analysis from the Center of American Progress :

[A]s a national problem, gun trafficking undermines state- and city-level efforts to reduce crime and violence. In this regard, the movement of crime guns tends to flow from states with weak gun laws to states with strong gun laws. For example, 2010 through 2020 ATF data show that 73 percent of crime guns recovered in New York—a state with strong gun laws—originated from out of state.

This problem, unfortunately, appears to be getting worse. ATF data show that 79 and 81 percent of crime guns recovered in the state of New York during 2019 and 2020, respectively, originated out of state. Moreover, the origin of these firearms supports the urgency of prioritizing oversight of the Iron Pipeline. ATF data show that in 2020, 53 percent of crime guns recovered in New York originated from six states with weaker gun laws: Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Virginia.

The McVeigh example points to a second reason to care about stolen firearms, which is that apart from being used directly in crimes, they can be sold to finance terrorist activity. Which brings us to our lax gun laws.

Gun Law Loopholes

Soon after McVeigh was discharged from the military, he wandered around the country and initially, Toobin writes, thought he might make a living selling things at gun shows — though he never had enough inventory to do so. He did have inventory following the Moore robbery, though, and gun shows were a natural place to unload the hot guns quickly and easily, since he could pretty much sell them to anyone who wanted to buy them, no questions asked. That’s because under federal law, background checks for firearms purchases are only required for federally licensed firearms dealers — they don’t apply to private transfers. Only 17 states require some form of background check prior to a firearm sale, regardless of where it takes place. But 33 states — including states like Nevada and Utah, where McVeigh sold his stolen weapons — do not. Because so many transfers between unlicensed dealers and individuals take place at gun shows (there are approximately 4,000 gun shows in the U.S. annually), this is known as the “gun show loophole.” The Gifford’s Law Center estimates that 22% of current gun owners obtained their firearm without a background check.

One of the most chilling parts of McVeigh’s story isn’t just how gun laws facilitated him in 1995, but how they would be even more conducive to such an effort today. McVeigh was taken into custody before he was ever identified as a suspect in the OKC bombing because he was stopped for driving without a license plate — and during the stop, the state trooper discovered that McVeigh was carrying a weapon without a permit in violation of Oklahoma law. Well, as of November 1, 2019, Oklahoma allows permitless carry. Which means that if McVeigh were stopped today under the same circumstances, there would be no basis for law enforcement to detain him.

“Gun Culture” and White Nationalism

Apart from the convenience they offered to translate stolen weapons into cash, the gun shows McVeigh attended illustrate the convergence of the obsession with firearms and white nationalist culture. Toobin notes that before social media was able to connect ideologically-aligned individuals at the click of a mouse, gun shows were where “thousands came not just for firearms, but for political solidarity.” In fact, McVeigh traveled the “gun show circuit” in the hopes of finding others who shared his outrage about the FBI’s raid in Waco, Texas — a sentiment which was, as Toobin describes, a part of a larger cultural milieu:

Gun shows were cultural events as much as commercial enterprises. They were celebrations of the gun as both a weapon and a symbol of political allegiance. Attendees were welcome to bring their own guns, though the weapons were supposed to be unloaded…At the big ones, there were explicitly political events, like panel discussions on such subjects as ‘What Do Bill and Hillary Have in Store for Gun Owners During a Second Term?’ and ‘The Future of Militias: What Will the Feds Do?’ Overall, as one study observed, ‘Political activities at gun shows represent views that start at the conservative and move right from there.’ The causes promoted at gun shows only began with Second Amendment rights, and they included closing borders, avoiding taxes, and defending the rights of Christians. Confederate flags and memorabilia abounded. So did right-wing literature.

What kind of right-wing literature, you ask? Well, Toobin writes that the one staple McVeigh always had with him at gun shows were multiple copies of The Turner Diaries, which McVeigh would give away if he couldn’t sell. The Turner Diaries are what Professor Belew describes as “the foundational how-to manual” for the white power movement. The basic plot involves a federal government controlled by Jews which passes a law called the Cohen Act, allowing the feds to confiscate all privately-owned firearms. In response, the book’s protagonist bombs the FBI building in Washington, D.C., which leads to a race war in which Jews are exterminated, Blacks and federal officials are lynched, and other minorities are deported. Toobin notes that McVeigh (who also later joined the KKK) first encountered The Turner Diaries in the advertisements of an NRA magazine called American Hunter.

Both Toobin and Belew emphasize that the themes of The Turner Diaries — unfettered gun ownership, hatred of federal law enforcement, perceived parallels between themselves and American revolutionaries, and a race war which will usher in an all-white Utopia — are all shared cultural touchpoints for the white nationalist subculture. Unfortunately, the narrative arc behind The Turner Diaries is not well known, and so acts of right-wing domestic terrorism are typically seen as one-off plots rather than attempts to put into motion a shared revolutionary goal. In 2010, for instance, the Hutaree Christian nationalist group was charged with seditious conspiracy for a plot to kill local law enforcement in an effort to instigate a larger war between themselves and the federal government. The judge threw out the charges, finding that the plan was mostly just hateful speech lacking a “unity of purpose” to resist the authority of the United States. My personal opinion is that the judge found this plot too incoherent mainly because she didn’t understand the larger cultural context of which it was a part. Had McVeigh been arrested “left of boom,” the idea that he planned to singlehandedly blow up a federal building in order to spark a larger uprising against the federal government may have also seemed pretty fanciful.

The most recent example of the enduring legacy and appeal of this white nationalist narrative is Massachusetts National Guard member Jack Texeira, who The Washington Post reports was both obsessed with guns and frequently spoke of a “race war.”

Right-Wing Media

It will shock no one to know that McVeigh consumed a steady diet of right-wing media — and this before Tucker Carlson’s white power hour on Fox News became a convenient one-stop radicalization shop. Toobin notes that while The Turner Diaries was McVeigh’s “lodestar,” his radicalization came through the following progression: NRA literature; the magazines Soldier of Fortune and Spotlight; propaganda-style documentaries like Waco, the Big Lie; a shortwave radio personality I had never heard of named Bill Cooper, and (surprise!) Rush Limbaugh. (An excellent window into the progression of radicalization through right-wing media is illustrated by the documentary film, The Brainwashing of My Dad.)

As far as I can tell, the common themes in all of these sources was constant fearmongering that the government was coming to take your guns. What happened at Waco? The government came for the guns. What happened in The Turner Diaries? The government came to the guns. What happened in 1994? President Bill Clinton signed the assault weapons ban and McVeigh decided to blow up a federal building because he believed the government was coming to get his guns.

The Rush Limbaugh connection, in particular, is relevant today. That’s because he had another fan, too: one Clarence Thomas, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. In fact, the Frontline documentary which aired a few weeks ago notes that an angry Thomas began listening to Limbaugh in the aftermath of his 1991 confirmation hearing — the same time period McVeigh was getting inspiration from Limbaugh for his attack. It stands to reason that the same hateful and extreme rhetoric which profoundly shaped McVeigh’s worldview would also affect Thomas’ — including on issues like gun rights, on which he would (and will continue to) have a say.

In 2020, a year before the January 6 attack, Trump awarded Rush Limbaugh the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Toobin writes that “[a]s president, Trump never explicitly endorsed the extremist presence among his supporters, but he knew how to speak to McVeigh’s successors in barely coded terms.” As much if not more than praising “fine people on both sides” of Charlottesville or telling the Proud Boys to “stand back and stand by,” awarding the person who fueled McVeigh’s grievances the country’s highest honor was undoubtedly understood by Trump’s extremist supporters as a tacit green light for political violence.

Political Denial and Deflection

Perhaps the most disappointing thru-line between the Oklahoma City bombing and today is Merrick Garland. Garland oversaw McVeigh’s prosecution, and made a deliberate decision not to highlight the larger extremist backdrop behind the event. In doing so, he solidified the “lone wolf” narrative surrounding the event that persists today. Notably, Toobin states that Garland never mentioned any thematic connections between Oklahoma City and January 6 during his interviews — and they haven’t been highlighted in the prosecutions against the Oath Keepers or Proud Boys, either.

This historic and current silence has only empowered those who want to downplay the domestic extremist threat. When President Bill Clinton called out Limbaugh, and right-wing extremist rhetoric generally, following the OKC bombing, Toobin writes that Limbaugh pushed back, claiming that “There is absolutely no connection between these nuts and mainstream conservatism in America today.” Later, under the Obama administration, Toobin describes Republican’s outrage to a Department of Homeland Security report on growing recruitment among domestic extremist groups in reaction to the election of the first Black president:

The report itself was less significant than the furious reaction to it — and the reaction to the reaction. John Boehner, then the highest ranking Republican in the House of Representatives, called the report ‘offensive and unacceptable,’ adding, ‘the Secretary of Homeland Security owes the American people an explanation for why she has abandoned the term ‘terrorist’ to describe those, such as al Qaeda, who are plotting overseas to kill innocent Americans.’ Representative Lamar Smith, of Texas, said the administration was ‘awfully willing to paint law-abiding Americans, including war veterans, as ‘extremists.’’ Representative Steve Buyer, the top Republican on the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee, said it was ‘inconceivable’ that veterans could pose a threat.

Following the criticism, DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano issued an apology and withdrew the report: “Embracing the mantle of feigned victimhood,” Toobin writes, “Republicans saw that they could deflect criticisms of and warnings about an affiliated movement by claiming discrimination.”

This tactic is most evident now in Rep. Jim Jordan’s Subcommittee on the Weaponization of Government (the name itself a wink and a nod to antigovernment extremists). His star witnesses last week included three former FBI employees who sympathized with Jan. 6 defendants or stonewalled investigations — one even lied about being in a restricted area of the Capitol on January 6. Jordan, however, has painted them as merely conscientious objectors who have been persecuted by the FBI for their political beliefs.

These “whistleblower” claims are fueling a larger efforts by MAGA Republican calls to “defund the FBI.” I suppose McVeigh would be glad his hoped-for revolution is finally getting underway — from within the federal bureaucracy he so despised.

Man, this was well-done. I think it took me 8 minutes to read on my phone yet there was so much connective tissue effectively connected.

Bravo, Asha (and Jeff Toobin)!

Excellent. Thank you Asha. I learned a lot. My friend, Dr. Erroll Southers wrote Homegrown Violent Extremism, which may be of interest to you and your readers.

https://books.google.com/books/about/Homegrown_Violent_Extremism.html?id=cyagBAAAQBAJ