Class 2. What is Propaganda, and What's the Problem With It?

Is there a such thing as "benign" propaganda?

If you are just joining The Freedom Academy, welcome! As a reminder, this post is a standalone “lesson” and you do not need to be caught up to follow along. I’ll reference any previous posts that offer relevant background, and you can always visit the syllabus and catch up at your own leisure. All class posts have an audio recording (see bottom) if you prefer to multitask while listening to me lecture!

Thanks to all of you who participated in the discussion question posted last Sunday. (For those of you who may have missed it, the assignment was to watch the video above and answer whether you would consider President Reagan’s speech “propaganda.”) It was such a thoughtful and nuanced debate that I’m tempted to hand off this week’s lecture to one of you as the comments hit many of the points and distinctions I want to make today! So let’s get to it.

As many of you noted, the discussion prompt is a bit of a trick question because as an initial matter, the answer depends on how one defines “propaganda.” There is no universally agreed upon definition of propaganda (that I’m aware of), but for our purposes I will use the one provided in Propaganda and Persuasion, 6th ed. (Garth S. Jowett & Victoria O’Donnell, Sage Publications 2015):

Propaganda is the deliberate, systematic attempt to shape perceptions, manipulate cognitions, and direct behavior to achieve a response that furthers the desired intent of the propagandist.

This is a very broad definition, and one that can be applied beyond political speech; it could bring within its scope, as many of you noted, things like corporate marketing. (It’s worth noting that commercial interests can be driven by political goals — for example, historian and UC Fresno Professor Blain Roberts has written about how the U.S. beauty industry emerged in the Jim Crow South as a way to entrench whiteness as a racial ideal.)

Using this definition, President Reagan’s speech would be propaganda: It’s deliberate and systematic — both in its language and imagery and in its purpose of reinforcing other pillars of Reagan’s foreign policy stance towards the Soviet Union. It uses facts and logic, but also bold, broad-brush claims, emotional appeals, and a “we’re the good guys” framing to persuade the audience to his position. The purpose of the speech was to be provocative, both in eliciting a response from the German audience on either side of the wall, but also from then President Mikhail Gorbachev. And, of course, the speech was delivered by a man who was known as the “Great Communicator” — his temperament and personality were reflected in the words chosen. There are so many excellent rhetorical analyses of this famous speech that I won’t attempt to dissect it in detail here, but this essay by Reagan’s speechwriter, Peter Robinson, offers a fascinating look at the thought which went into the crafting of it— and the intragovernment controversy it created behind the scenes.

[As an aside, this article about President Reagan’s invocation of the phrase “God bless America” is an interesting sidebar — he was the first president to ever close a State of the Union speech with that phrase (and I believe every president has done it since). The article notes that Reagan was attempting to build credibility with the evangelical base, which at that time was not squarely Republican. I have to think there was also an implicit jab intended at the “godless” Commies.]

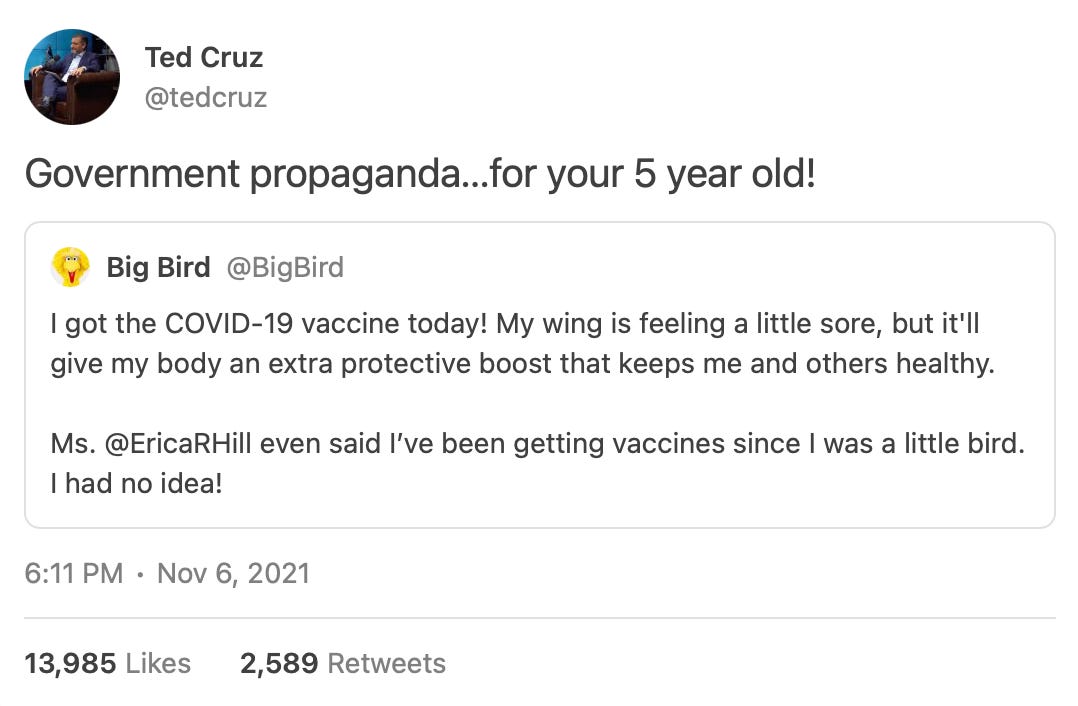

Still, it feels weird classifying Reagan’s speech as propaganda. After all, he wasn’t lying, nor was he being deceptive — he wasn’t obscuring, for instance, that he was speaking on behalf of the United States, as its leader. Many people think of “propaganda” in the pejorative sense, as speech that involves lies, manipulation, and distortion. In fact, it’s often leveled as an accusation to discredit messages from messengers with influence, like this attack by Ted Cruz on…Big Bird.

Big Bird’s intentions aside, it’s true that propaganda that has as its purpose an intent to mislead or deceive is different than what President Reagan was doing, which we might characterize as a more forceful, if biased, form of persuasion. But why? The following definitions, also from Jowett and O’Donnell, can be useful in distinguishing the two:

White propaganda comes from a correctly identified source, is mostly accurate, and attempts to build credibility with its audience. Reagan’s speech would appropriately fit under this category. (The authors also highlight Voice of America as one example of this type of propaganda.) Black propaganda, by contrast, “is when the source is concealed or credited to a false authority and spreads lies, fabrication, and deceptions.” Hitler’s Big Lie is the paradigmatic example most people associate with the word “propaganda," which is likely why it is associated with authoritarians, manipulation, and control. (Indeed, Texas A&M Professor Jennifer Mercieca calls this type of propaganda “persuasion without consent” and Yale Professor Jason Stanley has written about the formulaic structure and themes of authoritarian propaganda in his book How Fascism Works, which I highly recommend.)

Disinformation (coined from the KGB’s use of dezinformatsiya as an active measures tactic) is a form of black propaganda: It involves deliberately planting false or misleading information to deceive a target population. Two techniques often involved in disinformation involve using a deflective source, or a legitimizing source. A deflective source is basically a cover, concealing the true source of the message in order to garner more credibility. Russia’s fake Facebook ads in the 2016 election (which we’ll look at in depth later in the course) were deflective sources — they were designed to appear to users as though they were coming from authentic Americans. A legitimizing source is a cover used to seed false information, which is then referenced by the original source as “independent” or third party corroboration for the message — sort of a form of information laundering. The Patriot newspaper which ran the Operation Infektion story is an example of a legitimizing source; it was picked up and cited by a Russian outlet as corroboration for its story.

Although these terms and distinctions might seem academic, they are helpful in triangulating which elements of propaganda we find harmful, and which we find permissible in a marketplace of ideas. You say you want some examples of these techniques in practice? I’m so glad you asked! We have two home-grown case studies to look at involving our own former president:

Case Study #1: The Trump-Zelensky Quid Pro Quo

Most news coverage reported on former President Trump’s phone call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinsky as a corruption scandal — an extortion scheme or a shakedown. (Which it was.) But most did not examine it as an attempted disinformation operation. Here was how it went down:

The transcript of the “perfect phone call” relays Trumps conversation with Zelensky, and in particular, his concern with Ukraine’s role in the 2016 election and in the firing of the prosecutor who was investigating Hunter Biden and Burisma. Trump appears to condition the release of military aid to Ukraine, and a White House visit, on Zelensky’s promise to investigate both matters and “get to the bottom of it.”

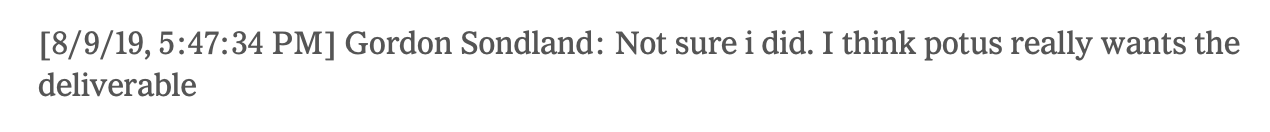

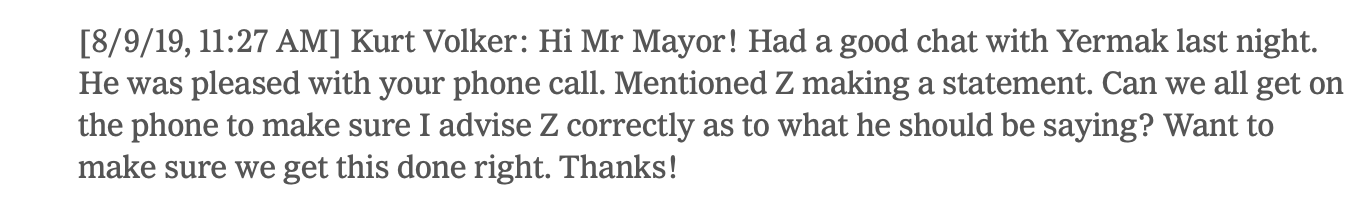

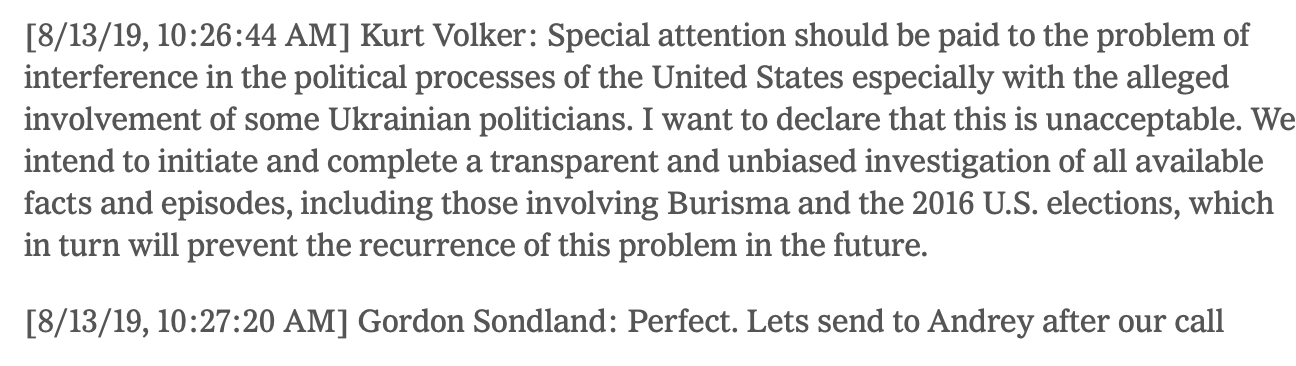

Text messages between Giuilani, Special Envoy to Ukraine Kurt Volker, and EU Ambassador Gordon Sondland, however, reveal that the goal was not so much an actual investigation, but the announcement of one. Volker and Sondland discuss that although Zelensky promised to look into the matter on the phone, Trump wasn’t going to be satisfied until he got the “deliverable” — for Zelensky to say so publicly.

Volker then confers with Giuliani to discuss what should go into Zelensky’s statement.

Based on Giuilani’s feedback, Volker and Sondland craft the following statement for Zelensky to make in a public setting, like a press conference (Andrey Yermak was Zelensky’s aide).

Importantly, the statement is not intended to be a joint statement between the U.S. and Ukraine, but to come from Zelensky alone. The statement was also intended to be disseminated to a U.S. audience: As diplomat Bill Taylor testified to Congress, Zelensky was expected to deliver the announcement in an interview on CNN. (An interview with Zelensky had in fact been scheduled with Fareed Zakaria’s show but was canceled after the whistleblower complaint became public.)

In short, Trump intended for Zelensky to state, on an American television network, that he was investigating two claims involving U.S. elections and persons — but in doing so, to conceal that he had both been asked to make the statement by the U.S. president and that the precise words of his statement had been crafted by members of Trump’s political campaign. Zelensky’s statement would have thus served Trump as a form of legitimizing propaganda, making it appear that another country had independently initiated an investigation into the 2016 election and Hunter Biden, thereby “corroborating” Trump’s own claims about both.

Case Study #2: Jeffrey Clark’s Fake DOJ Letter

Similarly, Trump tried to dupe the American public about the outcome of the 2020 election using the credibility of the Justice Department. In December 2020, Jeffrey Clark, a senior lawyer in the department, drafted a letter to be sent to the governor and other senior officials in Georgia. The letter falsely stated that the Justice Department was investigating “voting irregularities” in the state. The assertion is significant because under the Attorney General Guidelines, investigations require a factual predicate (i.e., they can’t go on a fishing expedition), so the letter implies that there was a factual basis to the complaints being investigated.

The letter goes further, advising Georgia legislators that they should convene a special session of the General Assembly to investigate these “irregularities” and “take whatever action necessary” to ensure a proper slate of electors on January 6.

The letter was intended to be sent against the backdrop of Trump’s lawyers (including Giuilani, again) presenting false evidence of voter fraud to Georgia legislators in an attempt to get them to change their slate of electors. As with the Zelensky phone call, a letter from the Justice Department would have served as legitimizing propaganda for Giuliani’s (and Trump’s) claims. It also would have provided legitimacy for Georgia to convene a special session of the General Assembly and call its slate of electors into question. (Clark never sent the letter because it was rejected by his boss, acting Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen; Trump’s attempt to oust Rosen and install Clark failed when several senior Justice Department officials threatened to resign en masse if he tried to do so.)

This concludes the tale of two U.S. presidents who engaged in propaganda. One did so overtly, to a foreign target, to serve national foreign policy goals. The other did it covertly, to a domestic target, to serve his own political interests. These three factors — transparency, audience, and purpose — animate our laws and policies towards propaganda, which we will turn to next week.

Audio Here:

Discussion Questions:

1. Imagine if either of Trump’s attempts in the case studies above had been successful. How would that have impacted media coverage, public perception, and domestic political events?

2. Why do the three factors differentiating Reagan and Trump — transparency, audience, and purpose — matter? Which one is most important?

3. What is the specific harm caused by propaganda that is incompatible with a democracy?

1. If either had been successful, we might be looking at a very different world - if the first has been successful, we might be living in Trump's 2nd term in office, in which (due to lack of support for Ukraine) Russia would have rolled over Ukraine and would be on the march in Eastern Europe. Distrust in elections (and therefore governmental institutions) would likely be even greater than it already is, among many other impacts. If the second had been successful, I think that would have plunged us into a constitutional crisis, in which (again) distrust in elections would be high, but I'm not sure how it would be resolved. Perhaps with more violence (a la January 6).

2. Transparency, or lack thereof, seems the key differentiator between the two. Reagan's speech, while slanted, was based in facts, while Trump's attempts were founded in lies. The source for the claims (of 2016 election interference by Ukraine, in the first example, and Georgia election irregularities in 2020, in the second example) were obscured and therefore hard to dispel quickly. So, we would be left with lingering doubts about the integrity of our elections.

3. If we doubt the integrity of our elections, then democracy will necessarily fall since the essence of democracy is representation through free and fair elections.

1. If he had succeeded in either example, the propaganda would have been normalized. It would have eroded the public faith in the media and crippled its role of investigating, exposing truth, and speaking to power.

2. Those three factors are intertwined. The audience and the purpose dictate the transparency – the tactic used. One tactic is the use of transparency or deception. Given that, I think transparency is the most important.

3. I think democracy thrives on white propaganda as long as it is more than one sided and open to debate. The dark, deceptive propaganda aims at society’s emotions in order to convince them the lies are in fact reality. The discussion is and becomes deeply one sided. Any debate, however tame, is classified as hostile. People feel it will all work out or get tired of fighting it and become quiet. That quiet allows the often-louder noise of lies to take up more space and eventually push democracy out of the picture.