Class 20. Inside the Troll Farm

The active measures playbook meets The Office.

One of this summer’s bizarre subplots in the ongoing war by Russia against Ukraine was the mutiny of Putin’s private mercenary warlord, Yvegeney Prigozhin. Following some Jerry Springer-like public exchanges between the two men, Prigozhin — who commanded the Wagner Group, a private military outfit, on Putin’s behalf in Ukraine, Syria, and Africa — led a half-baked march on the Kremlin, only to stop short of Moscow, turn around, and announce that he was retiring in Belarus…all within the span of 48 hours. It was like the writers for this season had nowhere left to go with the plot and had to quickly write a dead-end character out of the picture.

Well, speaking of dead and out of the picture, Prigozhin accidentally fell out of a window out of the sky last week, an outcome that surprised precisely no one. (Russia denies that Putin had anything to do with Prigozhin’s death, also surprising no one.) In looking back at his legacy, it’s worth remembering that, in addition to overseeing rape, torture, and the commission of other war crimes, Prigozhin was also a businessman. Specifically, Prigozhin owned and operated a catering company called Concord Catering — an enterprise that earned him the nickname “Putin’s chef” because of the food services he provided to the Kremlin and Russian armed forces — as well as an entity that became a household name: the Internet Research Agency (IRA), a.k.a. Russia’s troll farm. In February 2018, Prigozhin, his catering company (along with its sister company, Concord Management and Consulting), the IRA, and 12 other Russian nationals were indicted by Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller III for their roles in Russia’s disinformation operation during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Prigozhin was also sanctioned by the U.S. and even got his own FBI wanted poster:

Fun, right? For today’s lesson, we’ll take a trip down memory lane, looking at the inner workings of the IRA and the challenges faced by Mueller in bringing the troll farm’s activities to light through the criminal justice system…consider it all a post mortem, as it were, of the IRA, since it apparently no longer exists.

“Everything About the Place Was Strange”

I have to say that one of the first things that struck me when former employees of the IRA began to blab about what went on in there is how, on one level, ordinary it all seemed. Accounts from former trolls-turned-whistleblowers, like Vitaly Bespelov, described pretty typical office culture, like 8-12 hour shifts, crappy supervisors, and chatty smoke breaks. The building itself, a four-story office building located at 55 Savushkina Street in St. Petersberg, was completely out in the open and looked like any other building (the operation moved to sleeker quarters by 2018):

Inside, though, was a veritable Orwellian Ministry of Truth. In fact, the IRA got its start as a way to counter anti-Putin sentiment in Russia in the wake of protests following the 2011 Russian presidential election, which many in the country believed had been rigged in favor of Putin (imagine that). Noting that opposition leader Alexei Navalny was successfully using social media to rally sentiment against Putin, the Kremlin wanted to find a way to counter with pro-Putin messaging: In the words Bespelov, “The Kremlin decided they needed to make the online world and state television tell the same story.” Following the annexation of Crimea three years later, the Kremlin expanded on this strategy: Bespelov explains that his first assignment was to rewrite articles for fake Ukrainian news sites, replacing, for example, the word “annexation” with the word “reunification.”

“Bespelov concludes the point of all this was to complete what he calls a ‘circle of lies’ — a feedback loop where troll postings reinforced Kremlin news on state media, pushing one central idea which he characterizes as ‘Make Russia Great Again.’ In contrast to 2011, the internet and state media had now merged into one.” — VOA News

In other words, Russia learned the power of using the Internet for information warfare by first trolling…its own people. Well, practice makes perfect, so by the time of Brexit, and then the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the IRA was running an expanded, more finely-tuned operation that included a staff of close to 1,000 people assigned to different departments divided by region and tasks within the agency. (Bespelov also noted a separate graphics department, which created psychological memes called — this is my favorite — “demotivators.”) Workers were given assigned topics to write about along with rigorous daily quotas for their fake posts and comments.

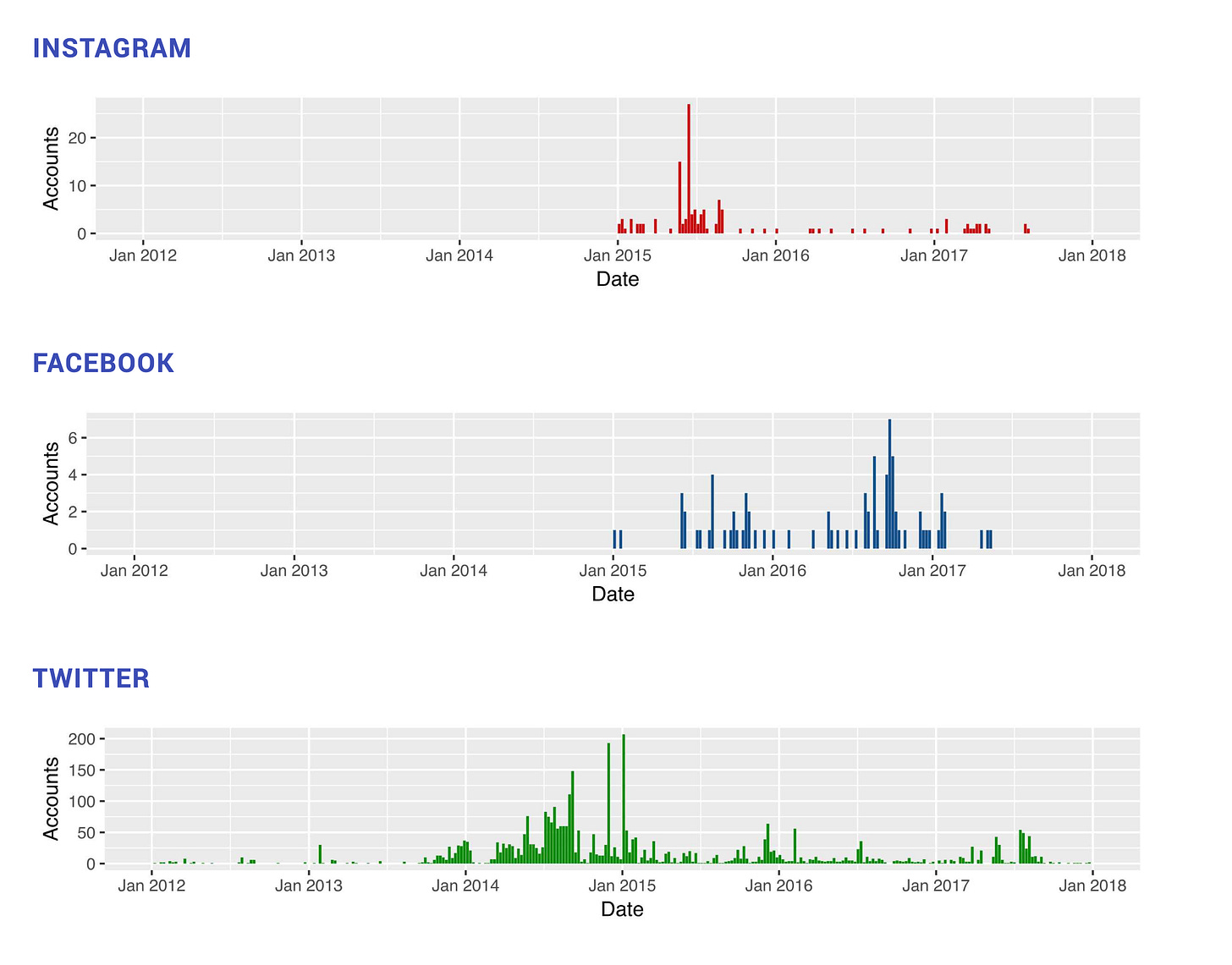

English speakers, who were the most highly paid in IRA’s operation, had to pass a written test to get hired, kept separately from other trolls, and instructed not to reveal anything about their work. We’ll be diving into the specifics of the influence campaign against the U.S., known as Project Lakhta, in a few weeks. But this really interesting report created by the data research company New Knowledge for the Senate Intelligence Committee in 2018 shows the dates of the first posts related to the 2016 U.S. election on various social media platforms:

Much of what we know about the IRA was uncovered after the 2016 election and Russia’s activities came to light through the Mueller and congressional investigation. But as the graph shows, the fake accounts targeting U.S. audiences were created as early as January 2015, and even January 2014 in the case of Instagram. Further, the IRA’s internal operations were well-documented in prominent U.S. sources like in this 2015 New York Times Magazine exposé…raising the question of why its influence operation in the U.S. seemed to take the FBI and intelligence community by surprise.

Trolling the American Justice System

Mueller indicted the IRA, Prigozhin, and fourteen other defendants in February of 2018. The indictment is worth reading in its entirety, especially since its primary purpose, as a “speaking indictment,” was to inform the public. After all, given that all of the defendants were in Russia, there was no real expectation that Mueller would get them into an actual courtroom or that they would end up in jail. As I’ll describe in more detail below, bringing criminal charges publicly also involved national security tradeoffs, which would have had to have been outweighed by some public benefit. When it comes to disinformation, sunlight is the best disinfectant, and public awareness of the operation was the main way to neutralize its effectiveness and put Russia on notice that the U.S. was on to its game.

There are a couple of interesting aspects to the charges and the facts underlying them. The first is the creative legal theory Mueller used for the case. Until the charges were filed, it was hard (for me, at least) to really see how Russia’s efforts ran afoul of the law — particularly if they were conducted remotely. In Class 3, we examined how we don’t really have laws that directly prohibit disinformation; the Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA) is the closest law we have that tried to ensure transparency for foreign government activities that involve speech. And since the trolls were operating out of St. Petersburg, it seemed that Russia wasn’t really directing and controlling “agents” on the ground here. Further, the FEC’s disclosure laws for political advertisements on TV and radio had not been expanded to include social media. So how, exactly, did Russia break the law?

Mueller’s answer was to charge the defendants with 18 U.S.C. 371, Conspiracy to Defraud the United States. (If the charge sounds familiar, it’s because it’s the same crime Donald Trump has been charged with for January 6.) This statute makes it a crime to conspire to “obstruct the lawful functions of the United States government through fraud or deceit.” How did Russia do that? The indictment lists three government agencies, including the Federal Election Commission, charged with regulating foreign expenditures in elections, the State Department, which is responsible for issuing visas, and the Justice Department, which is responsible for administering FARA. The indictment alleges that Russia’s scheme thwarted or attempted to evade all of these functions.

The conspiracy to obstruct the FEC is pretty straightforward: By posing as American accounts on social media, including through paid ads, Russia was attempting to evade the agency’s prohibition on foreign nationals making any “contributions, expenditures, independent expenditures, or disbursements for electioneering communications.”

But wait, you ask, what about the Justice Department — I thought there were no “agents” that would trigger FARA? Well, that’s the second interesting part of the indictment. When former CIA officer John Sipher comes and speaks to my class about Russia’s election interference, he always makes it a point to note that no matter how technical or remote Russia gets, it will always need intelligence collection on the ground. To that end, Mueller notes that:

Defendants and their co-conspirators also traveled, and attempted to travel, to the United States under false pretenses in order to collect intelligence for their interference operations.

a. KRYLOVA and BOGACHEVA, together with other Defendants and co- conspirators, planned travel itineraries, purchased equipment (such as cameras, SIM cards, and drop phones), and discussed security measures (including “evacuation scenarios”) for Defendants who traveled to the United States.

b. To enter the United States, KRYLOVA, BOGACHEVA, R. BOVDA, and another co-conspirator applied to the U.S. Department of State for visas to travel. During their application process, KRYLOVA, BOGACHEVA, R. BOVDA, and their co- conspirator falsely claimed they were traveling for personal reasons and did not fully disclose their place of employment to hide the fact that they worked for the ORGANIZATION [the Internet Research Agency].

c. Only KRYLOVA and BOGACHEVA received visas, and from approximately June 4, 2014 through June 26, 2014, KRYLOVA and BOGACHEVA traveled in and around the United States, including stops in Nevada, California, New Mexico, Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, Louisiana, Texas, and New York to gather intelligence. After the trip, KRYLOVA and BURCHIK exchanged an intelligence report regarding the trip.

d. Another co-conspirator who worked for the ORGANIZATION traveled to Atlanta, Georgia from approximately November 26, 2014 through November 30, 2014. Following the trip, the co-conspirator provided POLOZOV a summary of his trip’s itinerary and expenses.

In short, the defendants who entered the U.S. illegally and operated on the IRA’s behalf did so in violation of State Department regulations and FARA, and the overall operation, as noted above, tried to circumvent the FEC. The conspiracy charge was a great vehicle to bring in all of the different threads of the operation and tell the story to the American public.

However, what Mueller may not have been counting on was for Russia to fight the charges. Most defendants probably wouldn’t, especially if they worked for a foreign state and were out of the reach of U.S. courts. But one of Prigozhin’s companies, Concord Management and Consulting, retained counsel and decided to use the discovery process to force the government to reveal what it knew, and how it knew it. And here’s the kicker: Concord attempted to use what it learned through discovery to wage yet another information warfare operation.

Yes, that’s right folks, as laid out in this government opposition motion, Concord demanded that the U.S. lift its restrictions on the sensitive materials the government was providing in discovery — which were limited to Concord’s counsel due to national security considerations — so that it could disclose them to Prigozhin, the rest of the employees in his companies (including, presumably, the people who worked at the IRA), and the Russian Federation. Meanwhile, much of non-sensitive discovery that had already been provided had mysteriously found its way onto the internet, linked to a tweet on a newly-created account that said, “We’ve got access to the Special Counsel Mueller’s probe database as we hacked Russian server with info from the Russian troll case Concord LLC v. Mueller. You can view all the files Mueller had about the IRA and Russian collusion. Enjoy the reading!” Concord also stonewalled attempts by the Justice Department to serve subpoenas, concealed requested records, and produced a misleading affidavit from Prigozhin.

Basically, Prigozhin, through his company (and most certainly on Russia’s behalf), was attempting to weaponize the U.S.’s due process protections and troll the prosecutors in the process. The Justice Department said as much in its March 2020 motion to dismiss the case, stating that “Concord has demonstrated its intent to reap the benefits of the Court’s jurisdiction while positioning itself to evade any real obligations or responsibility.” The court agreed, dismissing the charges and ending the clown show Prigozhin was trying put on.

So what’s the story with the Internet Research Agency now? Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 it was still going strong, returning to its original focus of influencing Russian-speaking audiences, and expanding to new platforms, like Tik Tok. And as of May of this year, Prigozhin controlled about 15,000 accounts on the Russian social media platform VK.

That, of course, was before Prigozhin tried to stage his lame coup. In July, following the mutiny, the Kremlin began cracking down on Prigozhin’s companies, and claimed that the IRA had been disbanded. Curiously, though, on August 23, hours after reports of Prigozhin’s death, hundreds of social media accounts began posting messages, which were, according to CNN, “united in spreading two themes: Putin had no motive to kill Prigozhin, as the two had already resolved the issues related to Prigozhin’s mutiny, and that his presumed death was the work of the West, which opposes Wagner influence in Africa.” CNN notes that one post asked, “Why would Putin kill Prigozhin? (Prigozhin) was Putin’s friend who always helped him with every request. Therefore it was not beneficial for Russia to lose such a person.”

Looks like the IRA has a new CEO.

Audio here:

Discussion questions:

What were some advantages to the Kremlin of having significant parts of its influence campaign run by a private entity? Assuming the Kremlin has now absorbed the IRA into its own intelligence agencies, are there any benefits to having it under its direct control?

Since 2016, Americans have become more aware of foreign bots and trolls on social media platforms. Does this awareness effectively neutralize such operations and make them less effective or dangerous? Consider some of the precepts of reflexive control which we covered in Class 13.

Given that elections are especially vulnerable to foreign disinformation operations, where should responsibility lie for policing and regulating the social media space? The FEC? Congress? The social media platforms themselves?

1. As a separate entity, the kremlin had deniability. Absorbed, it has complete control.

2. No, it does not. It creates awareness but lacks any education and action steps that people need to properly address it. It is through that education that can give actual goals to accomplish. Russia should not be guessing what our goals are, we should be screaming them from the rooftops.

3. All of those should be responsible for monitoring the space and taking control. I think the FEC needs to stipulate what to tag and what to do about it. In addition, I think that Congress should have gotten involved with supporting the education of US citizens on what is happening, how to recognize it, and actions to take regarding it. It is in the power of a combined effort that we can take back control of the messaging.

Trolling? I find this report believable, but I could also be guilty of confirmation bias. Thoughts, Professor?