Class 27. Social Capital: The Dark Side

Weirdly, we are trusting each other more than ever...just in all the wrong ways.

If you are just joining The Freedom Academy, welcome! As a reminder, this post is a standalone “lesson” and you do not need to be caught up to follow along. I’ll reference any previous posts that offer relevant background, and you can always visit the syllabus and catch up at your own leisure. All class posts have an audio recording if you prefer to multitask while listening to me lecture!

I woke up on the morning of November 10, 2016 like half of the country: In fetal position with a hangover. The day before I had proudly worn my pantsuit and had taken my kids, then 8 and 10, with me to cast my vote for President of the United States. I was so certain that Hillary Clinton would win that I told them they could stay up late to watch the returns that night, and had invited my mom friends over to celebrate the election of America’s first female president. At around 9:30 p.m., things were not looking so good, and my fellow moms began leaving, one by one. I sent my kids to bed around 10 p.m. And then I stayed up until 3, nursing the bottle of wine that had been left untouched from the party, fielding texts from friends and family who couldn’t believe what was unfolding on the news. Here’s the before and after (even my cat, who I’m pretty sure was a Bernie Bro, was sympathetic):

When I checked Facebook the morning after Election Day (this is back when I still had an account, before I deleted it), a good friend had posted some thoughts about the election, and that it was an example of too much “bonding” and not enough “bridging” in the country. I followed up with her to ask her what she meant, and she referred me to Robert Putnam’s, Bowling Alone. That reading set me on the path that eventually became this class.

I introduced Putnam in Class 26 to discuss the concept of social capital and why it it is so crucial for a healthy democracy. But there is also a dark underbelly of social capital that has taken over America, and it is the key to understanding the erosion of our democratic social fabric.

Bonding vs. Bridging

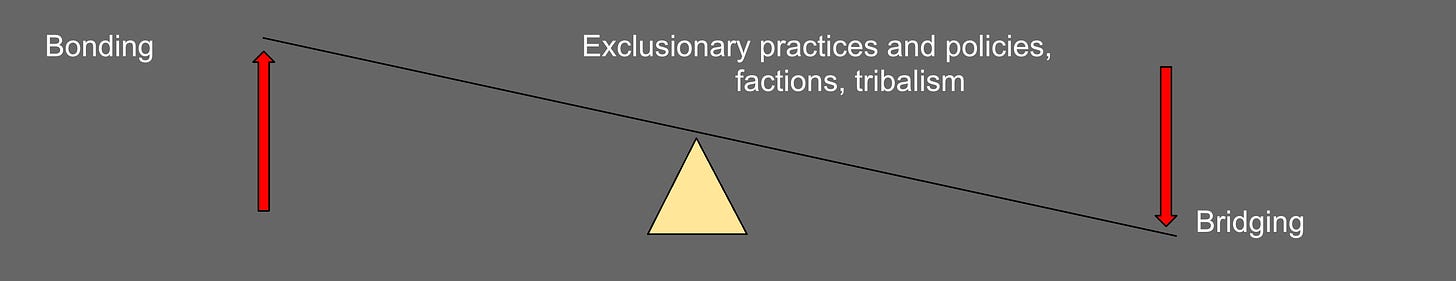

Putnam didn’t come up with the term “social capital,” which was already a well-known concept in sociology. He did, however, expand on the idea that we create social capital and social trust in one of two ways: By creating relationships with people like ourselves (bonding), or with people different than ourselves (bridging). Both of these are beneficial in different ways.

When I think about bonding social capital, I think about when my parents immigrated to America in 1970, in the first major wave of Indian immigrants to the U.S. following the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. A lot of these Indians were doctors like my dad, who came to fill shortages of physicians created by the Vietnam War. As a result, most did not end up in major cities, and folks like my parents often found themselves in areas where there wasn’t a huge Indian population. (I wrote about growing up as an Indian-American in Hampton Roads, Virginia, here.) So, what did my parents do? Well, they literally tracked down every other Indian who lived within an hour radius, of course! This small network of people in the same boat, as it were, was their cultural thread to the life they left behind, as well as a source of moral support, community, and camaraderie.

When I think about bridging social capital, I think about Yale University, where I work. Say what you want about “elite” institutions (and there is plenty to criticize about them), but one thing that these schools have the resources to do is to recruit widely — from all fifty states and around the world and across racial and socioeconomic groups — and offer financial aid to everyone who is admitted to give them access to the education they offer. As a result, Yale brings together thousands of students who come from a variety of different backgrounds that cross social cleavages. (To illustrate my point, consider that my alma mater, Yale Law School, admitted Clarence Thomas, Sonia Sotomayor, and Samuel Alito, who are diverse along a number of different dimensions.) These students are exposed to perspectives and beliefs beyond what they would normally encounter on their own in their interactions in and out of the classroom.

In short, bonding social capital serves as an important social safety net, while bridging social capital connects us to the wider world, introduces us to new ideas (which helps foster innovation), and expands our connections. In Putnam’s words, “[b]onding social capital constitutes a kind of sociological superglue, whereas bridging social capital creates a sociological WD-40.” (And to be clear, these are not mutual exclusive: Yale students, for instance, certainly “bond” as Yalies at sporting events, even as they individually “bridge” in classroom discussions.)

Here’s the thing: There are more negative externalities associated with bonding than with bridging. In particular, if there is an excess of bonding social capital, and a decrease in bridging social capital, you begin to see a society characterized by in-group and out-group divisions:

To understand why, we need to look at how each type of social capital generates different forms of trust and reciprocity.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Freedom Academy with Asha Rangappa to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.