Class 36. Feelings Don't Care About Your Facts

Fact checking isn't enough when the goal is being loyal, rather than correct.

If you are just joining The Freedom Academy, welcome! As a reminder, this post is a standalone “lesson” and you do not need to be caught up to follow along! I’ll reference any previous posts that offer relevant background, and you can always visit the syllabus and catch up at your own leisure. All class posts have an audio recording if you prefer to multitask while listening to me lecture!

It’s apropos that I am writing this lesson just as the pushback is growing against the Trump campaign’s false claims that Haitian immigrants in Ohio are eating cats and dogs. The pet eating hoax is a classic example of using a rumor as propaganda: The claim started off as misinformation (people repeating things they heard second or third hand, but apparently believing it to be true), and it has since morphed into disinformation, with people like Trump and J.D. Vance deliberately spreading the lie, knowing it to be untrue.

When we get to the last module of this course, Disinformation and the Lure of Authoritarianism, we’ll look at how spreading rumors is a tactic utilized to terrorize out-group populations. In India, the spread of fake rumors on WhatsApp about Muslims led to deaths and mob violence; commentators have noted that the deliberate amplification of the rumors about Haitians on social media has echoes of what happened on the airwaves in Rwanda and on Facebook in Myanmar. It’s pretty predictable that this kind of disinformation will lead to violence — Springfield has already had several bomb threats — but for the people spreading them, that’s a feature, not a bug.

For now, though, I want to look at why this lie persists, despite the fact that it has been debunked, repeatedly — local officials and even the governor of Ohio have stated that there is no credible evidence to support these assertions. Journalists have already traced the hoax to ground zero: Facebook (of course). And yet. And yet. Despite the voluminous amount of fact checking and corrective information the media, local and state officials, and Springfield residents have put out, the disinformation continues to have legs.

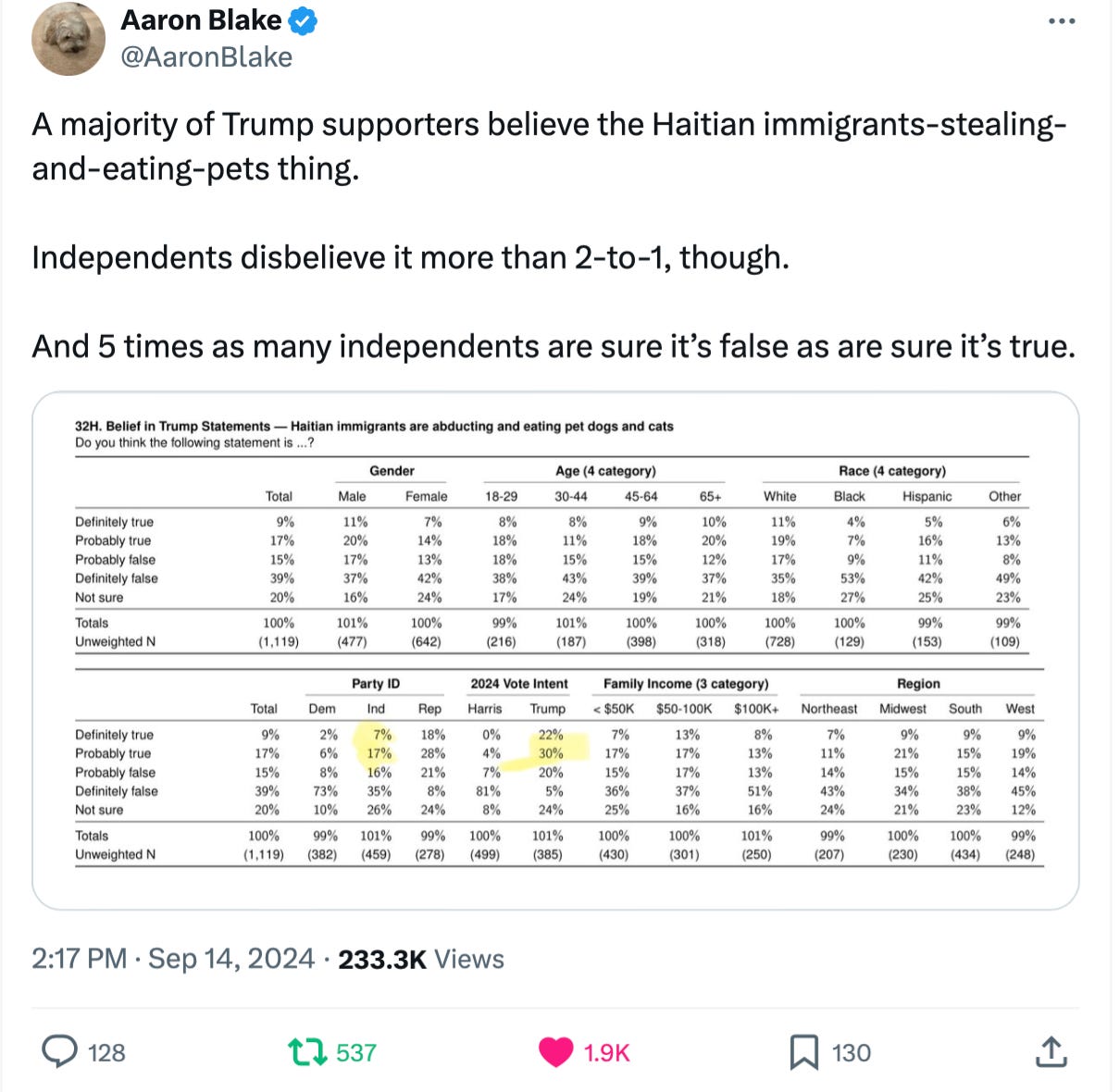

What’s really interesting, though, is that belief in the lie about Haitians eating pets varies depending on partisan affiliation. Take a look at the following table, tweeted by Aaron Blake of The Washington Post:

You’re probably not surprised. But the question is, why are people of different partisan affiliations processing information — including, presumably, corrective information — differently?

The best paper I have read breaking this phenomenon down is by D.J. Flynn, Brendan Nyhan, and Jason Reifler, called The Nature and Origins of Misperceptions: Understanding False and Unsupported Beliefs About Politics. It explains why, under certain conditions, people will reach the conclusion they want to reach, rather than the one they should reach based on the facts, and feel quite rational and justified in doing so.

So let’s break it down.

This is Your Brain. This is Your Brain on Political Tribes.

In Class 35, I had a conversation with author Andy Norman about how we can inoculate our minds against disinformation and false beliefs. Andy’s talk explained how we can strengthen our minds to engage in healthy questioning, evidence-based reasoning, and reflection and reassessment of our positions. In a cognitive utopia, people process information to find out what is objectively true, i.e., they are motivated by accuracy goals. In this kind of information processing, individuals evaluate all of the information available to them to reach the factually correct answer.

What Flynn et al. explain is that certain issues trigger directional goals when processing information, or “the desire to reach or reinforce a specific conclusion.” In directionally motivated reasoning, information is selectively accepted or rejected:

Directionally motivated reasoning leads people to seek out information that reinforces their preferences (i.e., confirmation bias), counterargue information that contradicts their preferences (i.e., disconfirmation bias), and view proattitudinal information as more convincing than counterattitudinal information (i.e., prior attitude effect).

Here’s the thing: Whether someone is motivated by accuracy or directional goals depends on the issue. The authors use something mundane, like purchasing a new appliance, as an example of a decision where most people are likely to research and take into account all the information to them. But what triggers directional motivations?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Freedom Academy with Asha Rangappa to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.