Class 44. Soup or Salad: The Challenge of the American "We"

Is it possible to create a national identity that can transcend our social and cultural cleavages?

If you are just joining The Freedom Academy, welcome! As a reminder, this post is a standalone “lesson” and you do not need to be caught up to follow along. I’ll reference any previous posts that offer relevant background, and you can always visit the syllabus and catch up at your own leisure. All class posts have an audio recording if you prefer to multitask while listening to me lecture!

“Since this is the last speech that I will give as President, I think it's fitting to leave one final thought, an observation about a country which I love. It was stated best in a letter I received not long ago. A man wrote me and said: ‘You can go to live in France, but you cannot become a Frenchman. You can go to live in Germany or Turkey or Japan, but you cannot become a German, a Turk, or a Japanese. But anyone, from any corner of the Earth, can come to live in America and become an American.’”

— President Ronald Reagan, 1988

I know it’s been a while since I posted a class lesson. My last module on the syllabus for the online course is “Building Resilience Against Disinformation,” which reflects the hope I had when I launched my Substack in November 2022 that by the time I got to the end of the course there would have been a lot of progress made on shoring up democratic guardrails, and that we would be in a very different place, politically, right now. Obviously, my calculations were…off. By the time we actually got to the last module this past January, I felt more than a little lost on how, exactly, we would build democratic resilience given the speed at which some of the most foundational institutions of our democracy were being attacked and dismantled immediately after the inauguration.

But, fear not, I’m back! For one thing, couldn’t just leave the course hanging with the last lesson currently posted on the syllabus, a talk with Professor Ruth Ben-Ghiat (and author of the Lucid Substack) rather depressingly called, “What the Road to Autocracy Looks Like.” I mean, we’re on that road now and leaving the syllabus there would basically mean just putting on sweatpants and giving up. But more importantly, I’m past my own ennui and ready to get back into the saddle, especially having just taught this class again to my Yale summer session, which reminded me of the more hopeful and forward-looking material that I normally end with.

For those of you who have been following the Substack course from the beginning, you know that we started with a deep dive into the goals of Russian influence campaigns, tracing them from the Cold War into the digital age. But the key, in my opinion, is understanding what makes America so vulnerable to them. After all, from an intelligence standpoint, the key to any covert operation is to exploit weaknesses. To that end, we switched gears and looked at things like racism, polarization, media fragmentation, and our own cognitive biases, all of which combine to create a perfect storm for disinformation to flourish.

All of these, though, are merely symptoms of a larger phenomenon which I covered in Part IV of the syllabus, which is the decline of social trust in America — or what political scientist and Harvard professor Robert Putnam calls “social capital.” (If you are new to The Freedom Academy, you can get an overview of social capital and why it’s critical to a healthy democracy in Class 26.) The key to social trust — the “generalized reciprocity” that makes us feel like we have the backs of our fellow citizens, and they have ours — is a sense that we are connected with a common purpose. The quote from President Reagan that I kicked off this post with seems to suggest that this common purpose is inherent in the idea of what it means to be “American.”

As we approach the United States’ 249th birthday, it’s worth asking: What does connect us all as Americans?

From the “Me” to the “We”

So I’m not the only one who has struggled with ending something with a major downer. Putnam’s Bowling Alone, published in 2000, chronicled the precipitous decline of social trust and civic engagement over the course of four generations since the end of World War II. Spoiler alert: The book’s conclusion was that at that moment, America was at a dangerously low level of social trust; the effects of the internet and social media had yet to be seen at that point, but Putnam was agnostic, or at best, cautiously optimistic, about where things would lead. Even so, let’s just say that after you put down Bowling Alone you will most likely have an urge to go change into sweatpants.

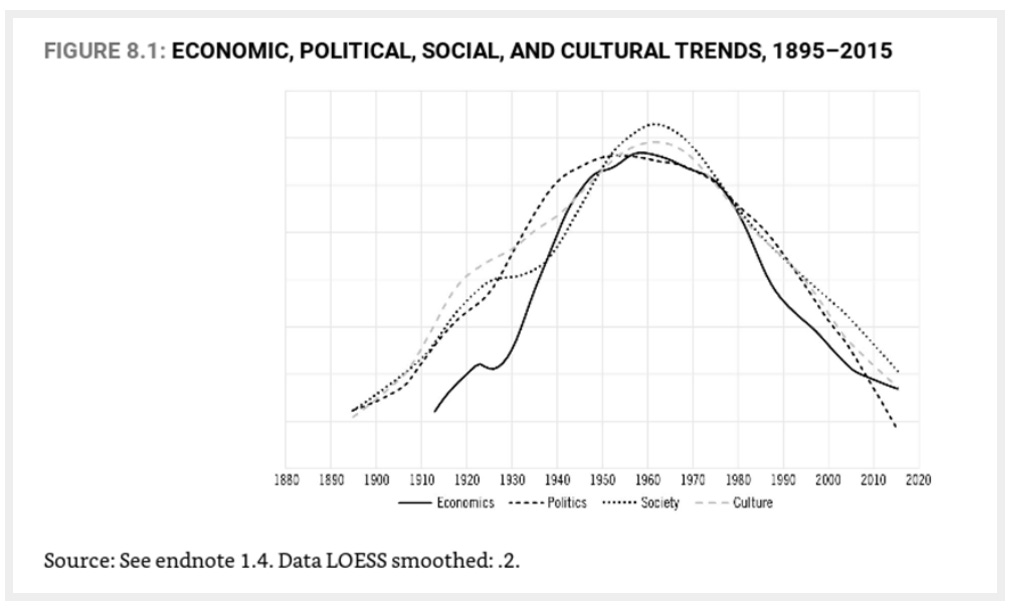

Perhaps feeling some guilt from basically predicting the end of democracy (especially as his implicit prophecy began to be realized), Putnam published a prequel to Bowling Alone in 2020. His thesis took the initial data presented in Bowling Alone — the high point of social trust and civic engagement culminating in the mid 1960s — and instead of looking at where we went from there, he looked at how we got there. What he found was fascinating, and it forms the basis of his book, The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again. The Upswing takes as its starting point the Gilded Age — an era marked by acute income inequality, xenophobia and nativism, rapid technological change, a surge of immigration, monopolists, oligarchs, and isolationism. Sound familiar? (Incidentally, the Gilded Age is Trump’s favorite era.)

From the Gilded Age, Putnam graphs changes in income inequality, bipartisanship in government, participation in community, civic engagement, and a number of other factors, and found a consistent pattern, to wit: An “upswing” which saw the creation of the New Deal, public education, more open immigration policies, progress in civil rights, social solidarity, and an overall marked shift from individualism to community culminating in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He characterizes this trend as an evolution from the “me” to the “we”:

Importantly, the upswing Putnam observes isn’t merely attributable to rallying around an “external enemy,” which can help spur a sense of collective identity: He notes that the upswing begins before World War I and, with a brief dip during the 1920s, then climbs again in the lead up to World War II. Rather, Putnam attributes the upswing to Americans organizing around common interests at the local level, which gains momentum through the Progressive Era and beyond.

I mean, that seems hopeful, right?

Are We Still a “Melting Pot”?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Freedom Academy with Asha Rangappa to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.