Class 50. Designing a Media Diet for the Information Age

If the media you consume were food, how healthy would you be?

If you are just joining The Freedom Academy, welcome! As a reminder, this post is a standalone “lesson” and you do not need to be caught up to follow along. I’ll reference any previous posts that offer relevant background, and you can always visit the syllabus and catch up at your own leisure. All class posts have an audio recording if you prefer to multitask while listening to me lecture!

We’re heading into the holidays, which means it’s almost New Year’s resolution season. That makes this lesson particularly apropos, as it examines how we can be more mindful about our own media consumption.

If we think about propaganda and disinformation as “cognitive hacks,” then it’s worthwhile to take a look at how we address actual, technical hacks — i.e., intrusions into technical infrastructure. The cybersecurity world of course looks at deterrence (preventing bad actors from trying to attempt to hack in the first place) and defense (putting barriers and guardrails in place so they aren’t successful if they try anyway). But ask any cybersecurity expert and they’ll tell you that getting hacked isn’t a question of if, but when. So part of cybersecurity also involves developing resilience: Assuming you will get hacked, how to you develop a capacity to recover from it quickly?

When we talk about disinformation (and especially foreign influence operations), we typically focus on deterrence and defense. For example, on the deterrence front, there are ways to make it harder to create inauthentic accounts, or to hold bad actors accountable, as the Justice Department did when it indicted Russian operatives who were using U.S. influencers to spread Kremlin talking points. There are also defensive tactics, like fact-checking, content-moderation on social media, and “pre-bunking” false narratives so that they don’t get traction.

But let’s face it, American brains have been hacked. A family member (who I will not call out, since they read this Substack) sent me a text last week that said, “George W. Bush is dead.” ??!? That seemed like big news — but I checked social media and, of course, nothing. So I asked said person to send me the link to whatever they were reading. When I went to the “article,” several subheadings on the piece were literally in Cyrillic. I pointed this out to said family member, telling them to be more careful about their media consumption and to keep an eye out for “clues” like, well, Russian subtitles. Their answer: “I read it on Facebook.” So, yeah, we need to build some resilience.

At this point, having read Careless People: A Cautionary Tale of Power, Greed, and Lost Idealism (a must-read, about Facebook/Meta) and sometimes peeking at the dumpster fire/cesspool which is now X, I’ve come to a few conclusions. The first is that I’m not sure social media platforms are really salvageable, at least not unless we burn them to the ground and rebuild them from scratch…which is not going to happen. As they are designed, most platforms are built to maximize “growth” and “engagement,” which means that their algorithms prioritize content that generates high emotional reactivity — usually outrage — resulting in more clicks, likes, and shares. Guess what can easily generate emotional reactivity? Propaganda and disinformation. Facts often tend to be boring. (More on that in Class 42.)

The second conclusion that I’ve come to is that we are only at the tip of the iceberg in understanding the mental health effects of social media. Part of the reason is that social media platforms have not been forthcoming on their own findings on this front, and also haven’t taken steps to reduce it — in fact, part of the “growth” and “engagement” revenue models is to make their products as addictive as possible, which in turn can have mental health consequences, including increased risks of depression and anxiety, particularly among younger people. Meta is currently facing a lawsuit on this very point by 42 attorneys general (yes, red and blue states!) on the marketing of its addictive product to kids. I predict that this will eventually go the same path as Big Tobacco did when all is said and done and the actual internal studies and smoking guns come out.

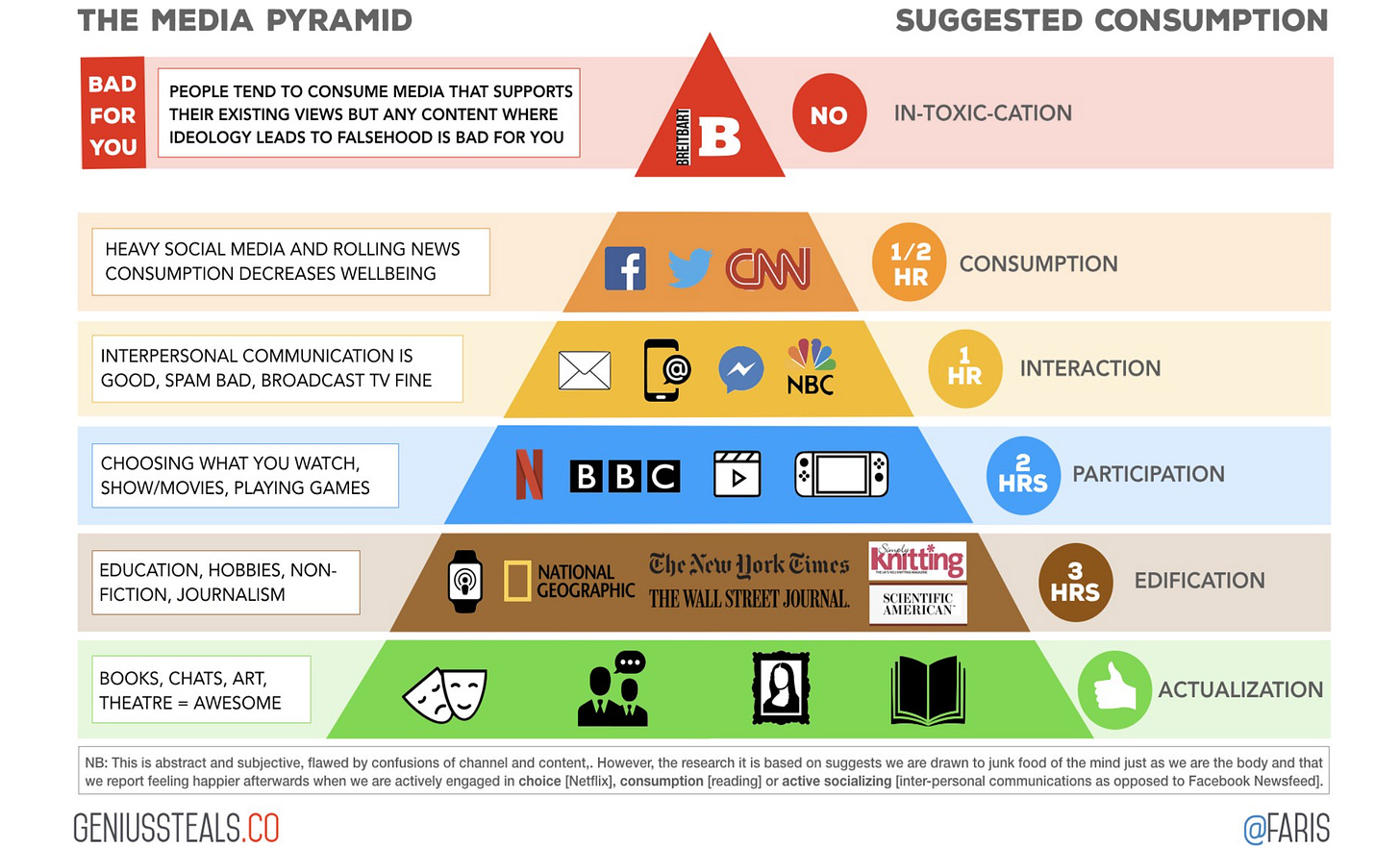

So if the upshot is that disinformation is here to stay and is akin to a public health crisis, how should we address it? One way is to offer some guidelines for healthy consumption, as the U.S. Department of Agriculture did in the 1990s with nutrition, through its “food pyramid.” The impetus behind the pyramid was to reduce Americans’ intake of saturated fats (lowering cholesterol was the health focus back then) — these were placed in the narrowest part of the pyramid, with the other food groups in increasing portions as you went lower. The point was to get people to be mindful of how much crap, like junk food and sweets, they probably included in their diet.

[NB: I learned from researching this post that the food pyramid was actually controversial when it was rolled out, mainly because the USDA had a vested interest in promoting the agriculture industry — which might explain why carbs and grains were at the bottom — and also because the dairy and cattle industry were mad that they were characterized as relatively unhealthy in large quantities. The pyramid underwent several revisions and now the food pyramid is a plate (i.e., pie chart). But I’m not here to debate the specifics — the main point is that the food pyramid offered a visual way for people to think about the relative portions they consumed from various food groups.]

That’s why I was intrigued by this media pyramid created by Faris Yakob for Genius Steals:

The temporal breakdown might seem like a lot, but on average Americans spend about 7 hours online every day (roughly half of that on social media, depending on age), so it does reflect time that could potentially be reallocated to other activities. In particular, you’ll note that the junk food and sweets include extreme internet sites and social media, which is where the vast majority of disinformation resides. From there, the pyramid increases in activities that integrate more interpersonal interaction, more personal control over consumption, more education and facts, and more real life experiences — all of which are both better for your mental well being and, by the way, for a healthy democratic society. Let’s start at the top:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Freedom Academy with Asha Rangappa to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.