Information Asymmetry and the Special Counsel

How bad actors weaponize institutional norms, and what Jack Smith should do about it. (SPOILER: With a poll at the end!)

Welcome back! I hope you all had a wonderful Thanksgiving (or relaxing weekend, depending on where in the world you are). This is my first post for all subscribers; the course, “Democracy in the (Dis)Information Age,” will start on Wednesday, and I will make that open to everyone this week, as well. I hope you will check it out if you have not already enrolled.

Last week, Andrew Weismann, a former prosecutor who worked on the team investigating the Trump campaign’s ties to Russia under Special Counsel Robert Mueller, wrote an op-ed for the New York Times. In it, he offered some prescriptions for the new Special Counsel, Jack Smith, who is now charged with investigating the higher-level players involved in the events of January 6 as well as the case involving purloined classified documents at Mar-a-Lago. The main thrust of Weismann’s advice was that Smith should learn from Mueller’s unwillingness to speak publicly about his investigation and not allow “only one side to shape the narrative.” Specifically, Weissman writes,

Neither the current special counsel regulations nor Justice Department rules require Mr. Smith to take a vow of silence with the American public. His ability to explain and educate will be critical to the acceptance of the department’s mission by the American public. It will permit Mr. Smith to be heard directly and not through the gauze of pundits and TV anchors; it will allow the public to directly assess Mr. Smith, a heretofore little-known figure; and it will permit Mr. Smith to counteract those strong forces seeking to discredit or misleadingly shape the narrative about the investigations.

What Weissman is referring to is information asymmetry. We’ll be discussing various types of asymmetries that facilitate disinformation in the course in the coming weeks, but here we can highlight the one at play here: Institutional norms and policies — which are ironically intended to protect democratic values — that create an information vacuum. Disinformation exploits these information vacuums, saturating the information space with “alternative facts” which can be very difficult to debunk once they take root.

The weaponization of silence

Mueller’s silence was exploited often during his investigation, mostly by Trump. But the most egregious example was former Attorney General Bill Barr’s deliberate three-week delay in releasing Mueller’s final report, during which time he released a “summary” of his own misleading characterizations of the investigation’s findings. To wit: Barr claimed that Mueller had found “no evidence of Trump campaign ‘collusion’” with Russia’s efforts to interfere in the 2016 election (conflating the higher standard of criminal conspiracy with the non-legal term, “collusion”) and that the ten instances of Trump attempting to interfere in that investigation did not arise to obstruction of justice. (We learned earlier this year, after a court ordered the release of an internal memo prepared by Barr’s Office of Legal Counsel, that Barr deliberately sought to fill the information vacuum with his own conclusions precisely because if the Mueller Report were released and evaluated on its own, it could be read as suggesting that criminal charges were warranted.)

In fact, Mueller himself was so concerned about Barr’s distortion of his findings that he wrote the attorney general a letter, diplomatically suggesting that Barr’s summary “did not fully capture the context, nature, and substance of [his] Office’s work and conclusions,” and that as a result, there was “public confusion about critical aspects of the results of [the] investigation.” And yet, Mueller did not speak publicly.

To be fair to Mueller, his silence was guided by longstanding norms of the Justice Department, in which prosecutors generally do not comment on ongoing investigations. In theory, this is a laudable principle: Allowing DOJ’s work to come in the form of formal filings protects both the integrity of the investigation and the rights of the accused.

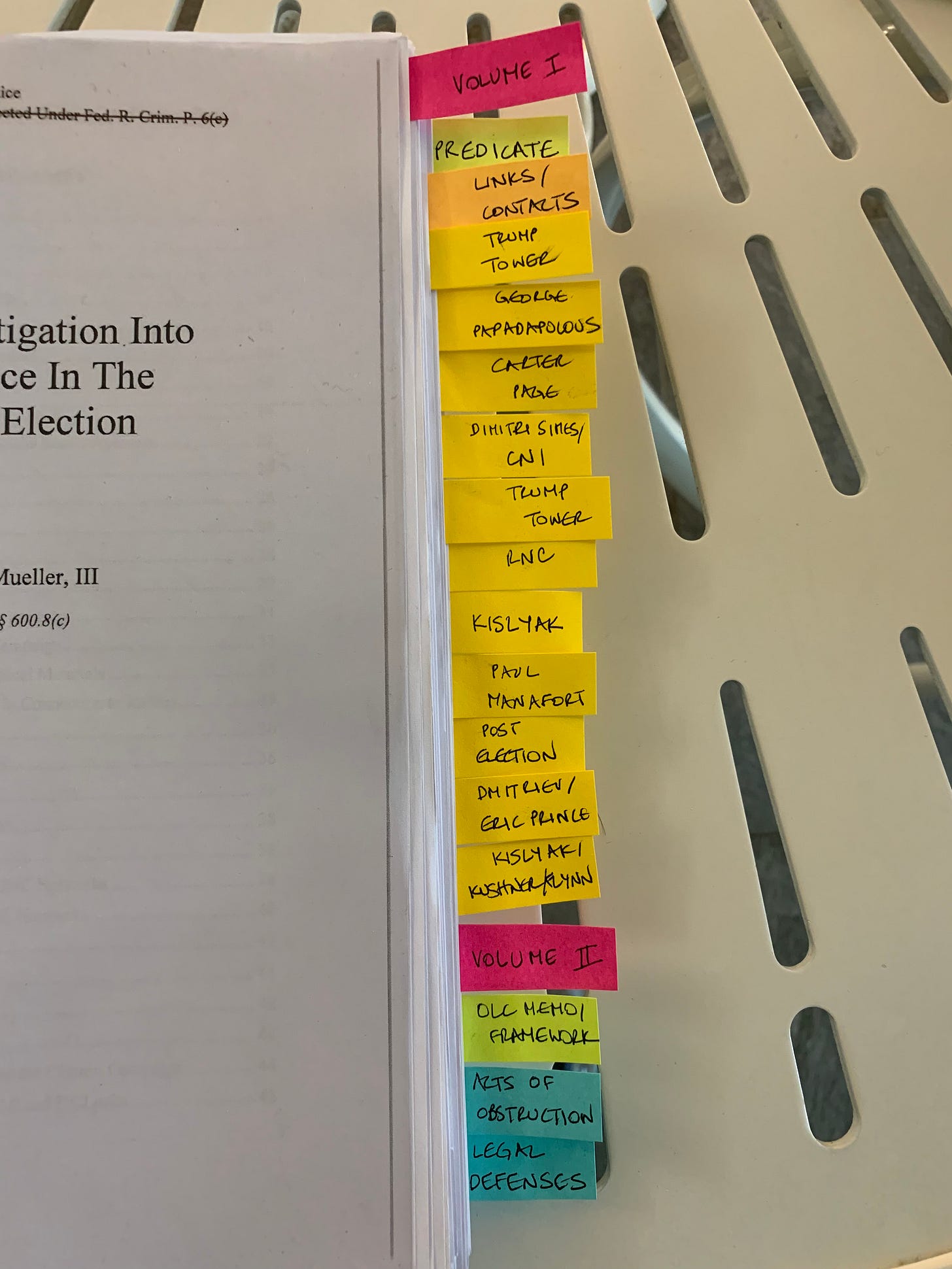

The problem is that Mueller’s attempt to allow his work to speak for itself didn’t compensate for the uneven information playing field he was on. Unlike most people, I read the Mueller Report cover to cover. And I’m not going to lie: It was a slog. It was a 400-page tome littered with turgid legal prose and was not particularly user-friendly for a non lawyer. (If you did not read the original report — and you would be excused for not doing so — the “expert summaries” I helped to edit for Just Security are a great Cliff’s Notes version to peruse.) There is no way that Mueller’s written findings were going to be able to effectively compete with Barr’s narrative, especially after the fact.

The informational asymmetry is especially pronounced in a situation involving the president of the United States (or even a former president with communications savvy, like Trump), who receives disproportionate media attention — itself because of a journalistic norm that if the president says something, it is ipso facto newsworthy. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson summed up the extraordinary megaphone enjoyed by the president in a 1952 case, Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, as follows:

Executive power has the advantage of concentration in a single head in whose choice the whole Nation has a part, making him the focus of public hopes and expectations. In drama, magnitude and finality, his decisions so far overshadow any others that, almost alone, he fills the public eye and ear. No other personality in public life can begin to compete with him in access to the public mind through modern methods of communications. By his prestige as head of state and his influence upon public opinion, he exerts a leverage upon those who are supposed to check and balance his power which often cancels their effectiveness.

The “modern method of communications” today involves technology that allows the president to reach millions of people within a matter of hours, making Jackson’s observation even more acute.

In short, Mueller’s approach ceded the information space to false narratives that still plague the public’s perception of his investigation. To this day — largely because of Barr’s “first mover advantage” in exonerating Trump (and Trump’s subsequent refrain of “NO COLLUSION NO OBSTRUCTION!” on social media and elsewhere) — many people believe that either Mueller did not uncover sufficient evidence to charge Trump with a crime, or that he had the opportunity to charge him but failed to do so. (Mueller’s more nuanced and legalistic conclusion was that despite the ample evidence of obstruction collected in the course of the investigation, due to the Justice Department’s internal policy that prohibited indicting a sitting president, he was unwilling to make a formal accusation in his report, deferring that decision to future prosecutors once Trump left office.) The perception of Mueller’s investigation as ineffective now colors how the public views the new special counsel, as well.

Prebunking: Leveling the information battlefield

Ultimately, Mueller undermined the main purpose of the special counsel, which is (in Mueller’s words), “to assure full public confidence in the outcome of investigations.” And here’s why: Barr, Trump, and others were counting on Mueller to observe institutional norms in crafting their strategy. They knew that, both because of his temperament and strict observance of institutional norms, he wasn’t going to correct their mischaracterizations publicly. Those assumptions have to change this time around: It’s clear that the old rules aren’t going to work in today’s information ecosystem. The key is to tweak them in such a way that they recalibrate perceptions without abandoning the principles on which the original polices are based.

On this front, the Biden administration’s handling of classified intelligence in the weeks leading up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is an excellent example. It’s clear that Russian President Vladimir Putin was counting on the U.S. government to follow its normal practice with any intelligence it had on his plans to invade Ukraine — namely, to keep its cards close to the chest, so as to protect highly sensitive sources and methods. Putin’s expectation was that he would have an information vacuum in which he cold not only deny his military plans, but also advance false pretexts to justify his eventual invasion. He guessed wrong.

In an unusual departure from its standard protocol, the Biden administration aggressively released classified intelligence revealing Russia’s military buildup, timeline for invasion, and planned disinformation campaigns. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken exposed Russia’s manufactured pretexts for war to the United Nations before Russia had a chance to promulgate them. This “prebunking” was critical in getting out ahead of Russia’s efforts and preventing its false narratives from gaining traction.

So far, there is no evidence that selectively leaking this intelligence has compromised our overall intelligence collection efforts, illustrating that with a slight shift in approach, the government can protect its interests and fight the information war.

The Justice Department should learn from this model and recognize that the rule of law is in a battle for hearts and minds: Perception matters. Ideally, it will adapt its policies and norms to allow (and encourage!) more engagement with the public on investigations of national interest — both to educate on procedural or legal questions and correct misconceptions (especially in advance) — consistent with its goal of protecting investigations and putative defendants. It’s time to recognize that the legitimacy of the administration of justice is shaped not only in the court of law, but also in the court of public opinion.

Poll!

I’m curious what your perceptions are of the appointment of the new special counsel, Jack Smith. Do you believe that his appointment is a good thing, for the administration of justice and the country? I’d love to know your expanded thoughts, questions, and concerns in the comments. I will do a post later this week responding to your feedback.

I get that Barr got his message out re the Mueller investigation and that this molded the public perception. What I don't understand is why the current DoJ didn't act upon Mueller's findings but instead buried the report. This only provides more ammunition for Trump and his cronies to further the “NO COLLUSION NO OBSTRUCTION!” narrative.

The last sentence: "It’s time to recognize that the legitimacy of the administration of justice is shaped not only in the court of law, but also in the court of public opinion." is a perfect summation of many of the issues we face when an information vacuum is filled with guesses and attempts to supply a preferential narrative.