Class 32. Why Turning Right Turned Out So Wrong (FREE WEEKEND BONUS)

Two roads diverged in a wood, and the Republican Party took the one less traveled by...and that made all the difference.

If you are just joining The Freedom Academy, welcome! As a reminder, this post is a standalone “lesson” and you do not need to be caught up to follow along! I’ll reference any previous posts that offer relevant background, and you can always visit the syllabus and catch up at your own leisure. All class posts have an audio recording if you prefer to multitask while listening to me lecture!

This is a lesson you won’t want to miss — which is why I am making it a free post for everyone! The material below is a great primer for our guest speaker this coming week, Yale Professor Jacob Hacker, co-author (with UCLA Professor Paul Pierson) of Let Them Eat Tweets: How the Right Rules in an Age of Inequality. If you’ve been watching the GOP jump off the cliff of democracy into the abyss of authoritarianism and have wondered, “How did this happen??!?” this post will help answer that question.

Here’s the bottom line up front: The Republican Party’s march to the far-right didn’t start with Trump. The seeds were planted several decades ago, but we are only seeing the full implications of it now (and, I daresay, we have not seen the end of it, which is going to be worse).

But let’s start at the beginning, or at least where we left off last time. In Class 31 we discussed how a strong “tribal” identity — feeling closely connected to a group with which we share some common feature — makes us think of people not as individuals, but in group terms: The in-group (“us”), and the out-group (“them”). This dichotomous thinking lowers our empathy for out-group members, and can also unwittingly make us more likely to be complicit in attitudes, actions, and behaviors which we might not otherwise hold or do on our own. These tribal dynamics are exactly the expected negative externalities of having too much bonding social capital in a democracy, which we looked at in Class 27.

So, here’s the million dollar question: In the U.S., what’s the feature that has the strongest tribal “pull”? It has to be something like religion, right? Or maybe race? Perhaps one’s cultural heritage? Hey, I know — let’s ask Daryl and Daryl:

Remember these guys? Their photo began circulating around 2018 — they were attendees at one of Trump’s rallies at the height of the Mueller investigation, and initially, their t-shirts were a little shocking. (I’m old enough to remember “Better Dead Than Red” t-shirts.) But they were really just an outward manifestation of a larger transformation in Americans’ self-identity, where political affiliation has become the most salient dividing line among us. I’m guessing that most of us wouldn’t be so shocked to see someone wearing that t-shirt today.

In fact, a 2017 study by Stanford professor Shanto Iyengar found that in America (and a few other democracies), bonds based on partisan affiliation have surpassed those based on race, religion, language and ethnicity. (You can take a quiz to see whether this is true for you, here.) As this Stanford Report notes, partisan group identity also allows for all of the worst parts of tribal behavior to come out:

[U]nlike race, religion and gender, where social norms dictate behavior – there are few, if any, constraints on the expression of hostility toward people who adhere to opposing political ideologies, the researchers said. For example, certain words are out-of-bounds when directed toward people of specific races or genders. But these boundaries don’t really apply in a partisan environment and, in fact, boorish behavior can actually be encouraged by party leaders.

Boorish behavior indeed. What’s weird is that it feels like it wasn’t this way until Trump came on the scene: I know when I worked at the FBI, for example, no one ever talked about their political ideology — I assumed most of my fellow agents hewed conservative, but no one had to “signal” their partisan affiliation in any outward way. Let’s look at why things have changed so dramatically.

The Conservative Dilemma

The common explanation of the roots of our current polarization is that it began with President Richard Nixon’s “Southern Strategy,” which appealed to the racial anxieties of working-class, white Democrat voters. What I found surprising in Hacker and Pierson’s book is their argument that this isn’t entirely accurate. Specifically, Hacker and Pierson argue that polarization and extremism go hand-in-hand with economic inequality, and that in this regard, Nixon — despite his racist dog whistles (like the “war on crime”) — kept extremism in check to some degree.

To understand why, it’s important to first distinguish between social policies — policies that center around cultural issues — and economic policies that benefit a large segment of the population. Hacker and Pierson observe that while pushing his party to the right culturally by capitalizing on the backlash to the civil rights movement, Nixon actually pushed them left on economic policy, expanding on New Deal programs like Social Security and even welfare: “On racial and cultural issues, Nixon was a harbinger of a new kind of Republicanism in the White House. On economic policy, he was the last social democrat of the twentieth century.”

What Nixon did was make a choice in what the authors call the Conservative Dilemma. The dilemma goes like this: Conservative parties in democracies are aligned with business and elite interests. They therefore have to deliver on these interests by promoting economic policies that benefit the very rich — the “plutocrats.” But in order to win elections, these interests have to be balanced against what is being delivered to voters. After all, your average working-class Joe isn’t inclined to vote for someone only interested in helping only the very rich. Therefore, one way the party can attract enough voters to be able to win elections is to temper its plutocratic economic agenda and ensure that they throw some bones to the middle and working class. There is no need, in other words, to go too far to the extreme on the cultural issues, because the party also has economic carrots to draw voters in. When this route is chosen, candidates are still generally competing on policy preferences and economic inequality is also kept in check. Let’s call this Door #1.

But conservative parties can instead choose Door #2: Pursue an economic agenda that benefits only the plutocrats — things like deregulation, reducing taxes, loosening labor laws, etc. — and helps the rich get richer, while cutting benefits for the middle and working class. This, argue the authors, is what began taking place starting in the 1980s under President Ronald Reagan, who began doubling down on plutocratic policies that benefited corporate interests and the superrich. Here are a couple of eye-opening graphs from the book, comparing income inequality in the U.S. to Western Europe from 1980-2016:

Unfortunately, once this fork in the road is chosen, the conservative party has an electoral problem. The plutocrats are only a small fraction of their voters. How do you get the rest of your voters to still vote for you, when they don’t benefit from the economic policies being pursued?

The answer is to double down on the cultural issues, and make your voters believe that these issues are existential — enough so that voters are willing to care less about their economic interests than in making sure that the culture wars are won. It was in this era that Republicans turned to groups like the NRA and evangelicals to mobilize voters through outrage on things like abortion, prayer in schools, gun rights, and immigration. These groups’ causes were amplified through right-wing media, which helped distract voters from — and encourage them to vote against — their own economic interests. (This attention displacement was the focus of the 2005 book by Thomas Frank, What’s the Matter with Kansas? How Conservatives Won the Heart of America.) I mean, who cares about health insurance when armed federal agents could storm your house at any moment and take your guns and force you to eat kale?

When faced with the Conservative Dilemma, the Republican Party latched on to division, rather than ideas, as a political strategy. In place of a commitment to shared policy positions, Republicans redefined their party as an identity based on “perceptions of shared allegiance and shared threat.” In doing so, it committed itself to the path that led to Trump:

[H]aving invested in division, GOP elites found that they had to keep on investing— not only to attract more voters, but also to respond to those voters’ radicalizing views; not only to identify scapegoats, but also to keep those they were scapegoating from exercising their growing electoral power. Republicans eventually discovered that the extremism they had unleashed to tackle the Conservative Dilemma was not theirs alone to control.

But while they couldn’t stop it, there was one person who definitely helped accelerate it.

Newtonian Physics Politics

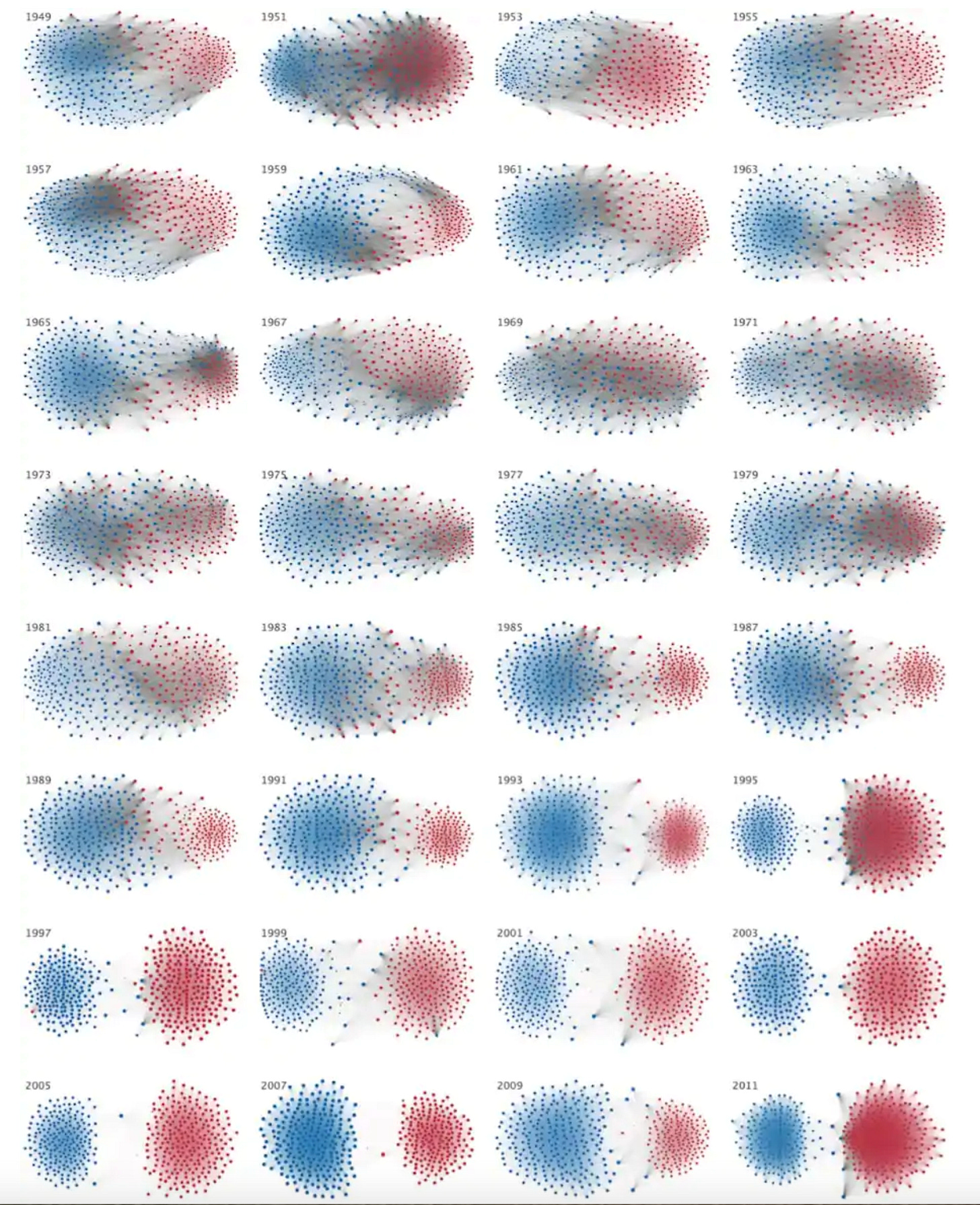

I can’t remember when I came across it, but this 2015 graphic from The Washington Post illustrating political polarization in Congress stopped me in my tracks. Basically, the graph depicts each Congress since 1949, with red dots representing Republican members, blue dots representing Democrat members, and lines connecting representatives who worked together. The amount of shading between the two groups therefore depicts the degree to which members crossed the aisle (i.e., bipartisanship) during that term. The Post piece describes the increasing separation between the two parties over time as a “picture of political mitosis,” which was an apt description:

I’d be interested to hear your thoughts in the comments, but to me the major inflection point begins in 1993, following the election of Bill Clinton as President. And then in 1995, you see a a dramatic split, where zero red dots cross the aisle. Anyone remember what happened in 1995?

Yeah, that was the so-called “Contract with America,” which ushered in a Republican-dominated Congress, and the election of Newt Gingrich as Speaker of the House. In his book, Burning Down the House: Newt Gingrich, the Fall of a Speaker, and the Rise of a New Republican Party, Princeton political scientist Julian Zelizer chronicles Gingrich’s rise to power and, in particular, how his successful takedown of Democratic House Speaker Jim Wright in 1989 broke democratic norms and guardrails that had helped keep polarization in check until then. Zelizer writes that Gingrich’s effort was unprecedented (no similar effort had occurred since 1910) because members of both parties knew that “[o]pening this door would trigger an unending cycle of retribution and generate a climate of total distrust.”

Rather than push back, however, the Republican Party went along with Gingrich. The fact that Gingrich was not only successful in his endeavor, but was rewarded for it soon after with the speakership itself, Zelizer writes, “created strong incentives for Republicans to ramp up their efforts and engage in more brutal fights.” We of course saw this in the late 90s with the impeachment effort against Bill Clinton, and the increasingly demonizing rhetoric used against the opposing party. In fact, in 1990, Gingrich wrote a memo to other Republicans called “Language: A Key Mechanism of Control,” which “recommended using certain words repeatedly like ‘corruption,’ ‘traitors,’ ‘sick,’ ‘radical,’ ‘shame,’ ‘pathetic,’ ‘steal,’ and ‘lie’ to describe the Democrats.”

In short, Zelizer observes, Gingrich departed from prior modes of governance which had valued bipartisanship to some degree. Instead, beginning with Gingrich, “[n]othing and nobody was sacrosanct,” and

…what did take root was the normalization of a no-holds barred style of partisan warfare where the career of every politician was seen as expendable and it was fair game to shatter routine legislative processes in pursuit of power….In Gingrich’s era, a crippling form of partisanship came to permanently define how elected officials dealt with almost every issue, ranging from who would lead the parties to mundane budgeting matters over war and peace.

This new era opened the door to a willingness to engage in what scholars have dubbed “constitutional hardball,” which refers to “tactics [that] are viewed by the other side as provocative and unfair because they flout the ‘go without saying’ assumptions that underpin working systems of constitutional government.” The willingness to engage in such tactics further breaks down democratic guardrails, and advances extremism and polarization.

Yeah Sorry, It’s Not “Both Sides”

If there is one thing that drives me absolutely nuts these days, it’s the inability or unwillingness of most mainstream media to acknowledge that extremism, and the motivations behind it, are heavily tilted to side of the political spectrum. Notice I didn’t say it only exists on side of the political spectrum — there are indeed kooks and extremists and crazies “on both sides.” But the salient question is where the center of gravity lies on either side of the partisan divide. And on this point, the parties are not the same.

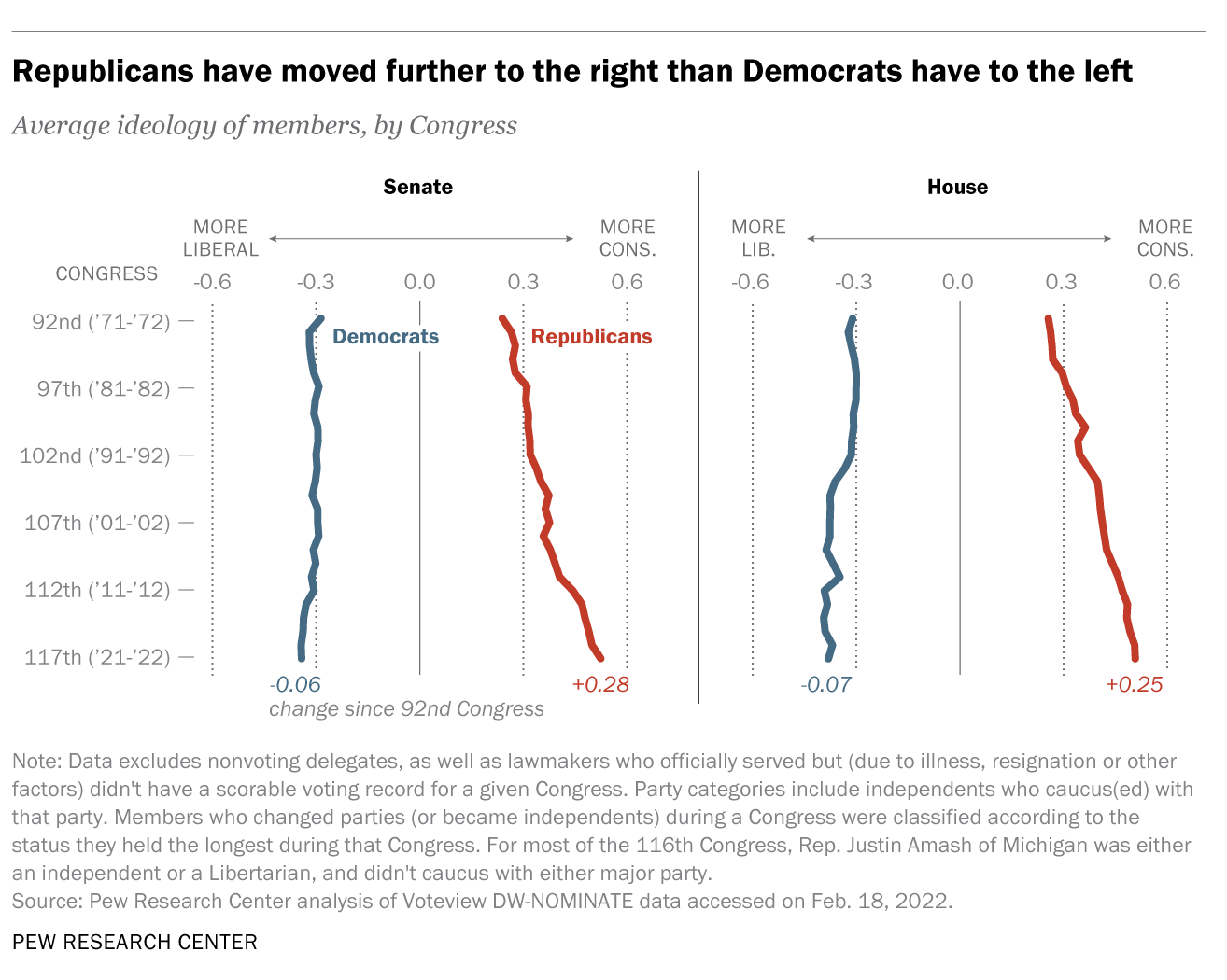

In fact, a 2022 Pew Research study observed that while both parties have moved farther away from the center and the partisan divide is higher than it has been in over 50 years, the degree of polarization is asymmetrical:

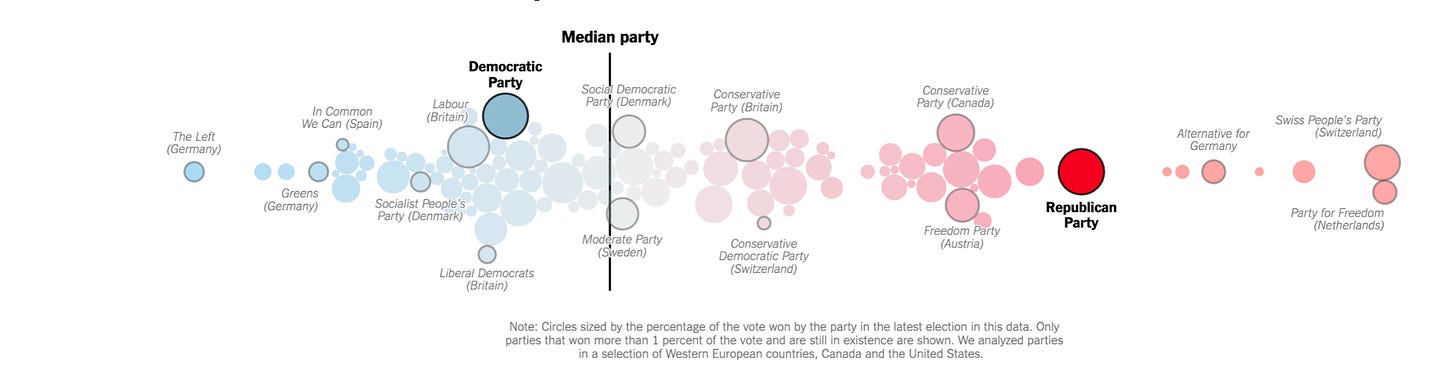

This asymmetry exists even when comparing the American right and left to liberal and conservative parties around the world. The following graphic from a 2019 opinion piece in The New York Times by Sahil Chinoy shows where the center of gravity on the right and left fall in the U.S. compared to other countries. Chinoy analyzed words used in the platforms of each party to measure their distance from the center, and the size of the circles are based on the percentage of the vote won by the party in that country’s election. You can see that in the U.S., the Republican Party is not only farther to the right of other countries’ conservative parties, but that “far-right populist parties [in Europe] are often an alternative to the mainstream. In the United States, the Republican Party is the mainstream.”

Again, this graphic is from 2019, and I would venture that both the U.S. and European conservative parties have shifted even farther to the right since then.

Republican “identity politics,” which mobilizes voters using culture wars and encourages divisive, tribal thinking and behavior, combined with elected officials’ willingness to engage in constitutional hardball tactics, essentially create a self-perpetuating cycle of extremism, polarization, and democratic dysfunction. In fact, Hacker & Pierson observe that this cycle can benefit Republicans, because voters find it difficult to isolate the causes of government dysfunction and typically end up blaming the party that is “associated with an active use of government (that is, Democrats).”

As of the writing of their book in 2020, Professors Hacker & Pierson did not feel all was lost. But they noted that the corrective path needed to begin “with a decisive electoral defeat for Trumpism,” followed by economic policies that begin to address economic inequality. Well, Trump lost, but Trumpism clearly hasn’t. And I’m not sure there have been the kind of economic reforms the authors had in mind. Tune in on Tuesday for our discussion with Professor Hacker on all of the above and we’ll find out whether his democratic prognosis has changed since then. (Have your sweatpants ready, because I have no idea how depressing it will be!)

In short, as the system is designed right now, there’s no real downside for the democratic backsliding we are witnessing — at least for the party that is causing it. And that’s why the polls are suggesting that Trump may very well take the White House again this December.

Great piece. Have an observation/question about tribalism. You write:”In fact, a 2017 study by Stanford professor Shanto Iyengar found that in America (and a few other democracies), bonds based on partisan affiliation have surpassed those based on race, religion, language and ethnicity. (You can take a quiz to see whether this is true for you, here.) As this Stanford Report notes, partisan group identity also allows for all of the worst parts of tribal behavior to come out:

My observation is that these affiliations cited above don’t include the tribalism around sports. This has been a source of extreme tribalism and boorish behavior forever, it seems. The sports “arena” provides both the norms of rules, regulations, and “sportsmanship. But they also tolerate, cultivate, reward, and hence normalize everything from the fanatical WWE fans, to the British soccer hooliganism, to hockey fans who attend for the fights, and so on ad infinitum.

My point is that Trump’s schtick is very WWE. In a sense, one could argue that his populist appeal is based on bringing the norms of the WWE into politics. The WEE is all about the cathartic opportunities of being extremely tribal around transparently fantastical characters and story lines. Isn’t this what MAGA is all about?

At the risk of being ridiculously simplistic, I think the common thread is resentment, and a choice, whether realized or not, to have a cynical, dark vision of life, rather than an optimistic, generous vision of life, and the dark side is gaining...all the old sayings, glass half full or half empty, etc., have real meaning and implications; we need The Carter Family's "Keep on the Sunny Side of Life" back into the American spirit.