Discover more from The Freedom Academy with Asha Rangappa

Class 8. The CIA and the Cultural Cold War

The CIA used art, music, and even tabloid gossip in the psychological battle against Communism. Was its covert use of cultural weapons inherently antidemocratic?

Some inside the CIA began to recognize a basic problem in its approach to the ideological confrontation that was the Cold War, barely a decade after fighting had stopped in Europe: focusing on the strengths of the Soviet Union meant neglecting one’s own strengths. ‘Concentration on the enemy’s techniques has tended to result in the overlooking of potential psychological weapons which originate in, and are peculiar to, the free world,’ the CIA wrote in one project outline.

— Thomas Rid, Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare

As I was researching for this week’s post, the above passage stood out to me since we are coming on the heels of a lecture that focused mostly on the strengths of Soviet, and now Russian, active measures operations. I know that my last few lectures have been kind of down on the U.S. for its lackluster response to foreign propaganda and disinformation, both historically and in the present. So I thought I’d switch it up a little this week and offer a window into a little-known aspect of the U.S.’s covert operations during the Cold War in its ideological battle against Communism. It’s a cool, fun, and mostly positive segue into our guest lecture next week, which will involve a discussion with author Tim Weiner on the CIA’s successful covert operation in Poland, QUHELPFUL.

If you’ve ever been to an improv show or watched one on TV, you know that the performers solicit ideas from the audience upon which to build an impromptu, unscripted scene. I dabble in improv myself, and one of the things you’re taught is that when you get a suggestion, you don’t want to go from “A” to “B,” you want to go from “A” to “D” — meaning, you don’t want to interpret the topic literally, but rather use it as a springboard to brainstorm something that is two or three degrees removed from the original concept, but still retains the concept’s essence.

So, imagine if someone yelled out the word “freedom”…what might you showcase that evokes that idea, without actually saying it directly?

The CIA’s answer to this exercise in abstraction was abstraction itself. That is, the agency believed that particular forms of cultural expression in the West, including modern art, jazz music, and even tabloid gossip and astrology, could provide a subliminal counterweight to Communist ideology. You might think it silly — I personally find it brilliant — but it’s worth understanding as we contemplate our own strengths vis a vis Russia and other adversaries today. More than anything, the “cultural Cold War,” as author Francis Stonor Saunders has dubbed it, speaks to a certain type of creativity and ingenuity in a strategy to win hearts and minds. It also highlights troubling questions about the ethics of engaging in psychological warfare in a democracy.

But first, let’s turn to the op.

The Vaporings of Half-Baked Lazy People

One of the first people to join the CIA shortly after its creation in 1947 was Thomas Braden, a former executive director of the Museum of Modern Art. He was put in charge of the agency’s “cultural activities.” His arrival coincided with the demise of the State Department’s overt promotion, alongside MOMA, of American modern artists in a traveling exhibit called “Advancing American Art.” The exhibit was shown in countries that spanned Eastern Europe, Latin America, and the Caribbean and featured artists like Georgia O’Keefe and Adolph Gottlieb. The idea was to use American art as a tool of diplomacy — but the tour was canceled after the exhibit received negative press coverage and faced public backlash.

Part of the public objection to using taxpayer money to showcase American artists was because modern art lacked popular aesthetic appeal; President Truman, an admirer of Realists like Rembrandt and Holbein, reportedly described modern art as “merely the vaporings of half-baked lazy people.” But support for the public-private partnership waned for another, more political reason: The perception that modern artists themselves were Communist sympathizers. This assessment wasn’t that far off; Saunders notes that Gottlieb, as well as artists like Jackson Pollack and William Baziotes, had been Communist activists. According to Saunders, Missouri Republican George Dondero went so far as to “declare modernism to be quite simply part of a worldwide conspiracy to weaken American resolve.” She continues:

Dondero’s neurotic assessment was echoed by a coterie of public figures, whose shrill denunciations rang across the floor of Congress and in the conservative press. Their attacks culminated in such claims as ‘ultramodern artists are unconsciously used as tools of the Kremlin’, and the assertion that, in some cases, abstract paintings were actually secret maps pinpointing strategic United States fortifications. ‘Modern art is actually a means of espionage,’ one opponent charged. ‘If you know how to read them, modern paintings will disclose the weak spots in US fortifications, and such crucial constructions as Boulder Dam.’

(I hope I’m not the only one wondering if these members of Congress are distantly related to Marjorie Taylor Greene and Jim Jordan.)

Ironically, modern art — and Abstract Expressionism in particular — was a reaction to the Socialist Realism style, then popular the Soviet Union. What is Socialist Realism, you ask? Basically it was government-sponsored propaganda that depicted the virtues of Communism: It portrayed the proletariat engaged in typical, but idealized, scenes of Soviet life. As far as I can tell, it often involved people schlepping stuff. Here’s an example — big strong men carrying a huge log…looks fun!

Big strong woman carrying a shovel!

Happy people carrying…hoes (? I think)!

I don’t know about you, but just looking at these paintings makes me exhausted. I feel like I just got off of a stairmaster.

Anyway, it’s easy to see why the CIA saw an opportunity in Abstract Expressionism. Saunders describes the CIA’s view:

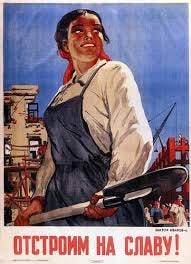

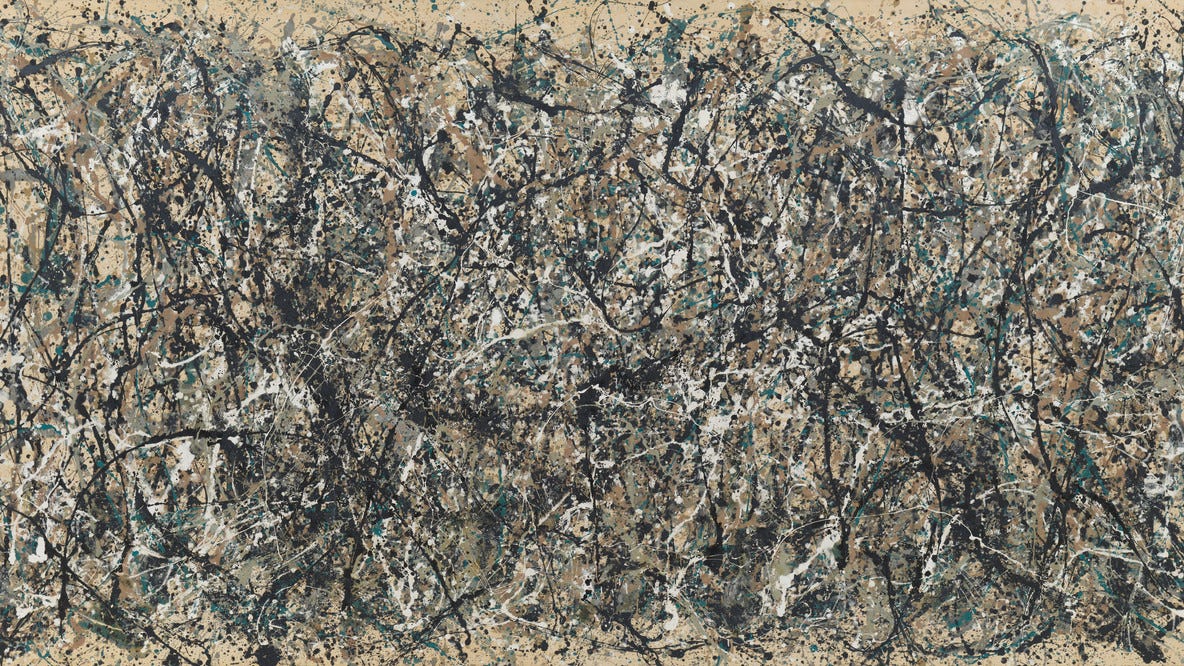

Where Dondero saw in Abstract Expressionism evidence of a Communist conspiracy, America’s cultural mandarins detected a contrary virtue: for them, it spoke to a specifically anti-Communist ideology, the ideology of freedom, of free enterprise. Non-figurative and politically silent, it was the very antithesis to socialist realism. It was precisely the kind of art the Soviets loved to hate.

Why would the Soviets hate Abstract Expressionism? Well, I’m not an art expert, but I have to say that if I were a a Soviet artist who was forced to paint people hauling tools all the time I’d be kind of envious of someone who could paint this without being sent to a gulag (I personally find the colors soothing, too):

Now take this Pollack. Not exactly soothing, but definitely not realistic, nor constrained. Saunders quotes art critics describing Pollack as “‘the triumph of American painting’, which spoke for what America was: vigorous, energetic, free-wheeling, big.” If I had to give it adjectives I’d call it “rambunctious” and “undisciplined.” Definitely not Politburo-approved.

In short, the retreat of the State Department in its overt support for modern art opened a door for the CIA to pick up the baton and do so covertly. Operating through a front organization called the Congress for Cultural freedom and with MOMA as a cutout to add another layer of plausible deniability, the CIA indirectly funded artists in thirty-five countries who (unwittingly) advanced American interests.

The covert patronage of the arts raises some interesting questions about what “freedom of expression” means in the psychological warfare context, and I’ll get to that in a bit. But what I think is one of the most interesting parts of this story is that the intended target audience wasn’t the Soviet masses, but other artists — people who were themselves the producers of Soviet propaganda, or artists in the West who could be sympathetic to it. Reminding them of the rigidity and conformity of Soviet life planted a seed of subversion into the Soviet’s own weapons of information warfare.

A Blue Note in a Minor Key

I have to say that I went down some rabbit holes trying to find “Soviet music” to get a sense of what people would have been listening to in the U.S.S.R. in the 1960s and…hoo boy. Here is what I found (I wrote to some friends who are Soviet experts so I may update this video if they get back to me with some better stuff):

It’s basically the schlepping tools paintings in musical form. Not hard to see why he following, in contrast, could be considered highly subversive, and therefore very useful to the CIA:

The CIA’s use of jazz music as a part of its cultural warfare arsenal echoes, in some ways, its use of modern art. Like Abstract Expressionism, jazz music rejects rigidity and conformity, is rebellious in form, and celebrates improvisation, and experimentation — all subversive qualities in a Communist regime (and which is probably why jazz, along with other “decadent” music, was banned from Soviet airwaves during the Cold War).

But jazz departed from the art context in two important ways. One is that unlike Abstract Expressionism, jazz had broad popular appeal, and wasn’t categorically associated with Communist ideology. This meant that jazz could be used as both an overt tool — as it was by the State Department — as well as a covert tool by the CIA.

The second departure from the art context is more complex. Part of the reason the U.S. government employed jazz as a tool of cultural warfare was specifically to counter the Soviet’s highlighting of racism in America. The idea was that by sending Black musicians around the world (especially to perform with white musicians), the U.S. could present an image of racial harmony. Of course, the idea of using Black music to obscure real racism against Blacks in the U.S. is highly problematic. This put Black musicians, in particular, in a complicated dilemma: They were being asked to present an image of their country which didn’t reflect their lived experience. An exploration of this paradox is presented in a PBS documentary called The Jazz Ambassadors.

Overt propaganda at least gave artists a choice in whether to participate in furthering the government’s objectives. Louis Armstrong, for example, initially refused to participate in State Department-sponsored musical tours of Africa — and only later reluctantly did so after legal progress was made on civil rights. But the moral and ethical dimension gets even more complex when it involved Black musicians who became unwitting propagandists for a picture of the U.S. that they did not believe in. One example is musician Nina Simone, who in 1961 was sent to do a musical tour in Nigeria by the American Society of African Culture — a CIA front association — as part of a covert operation to sway the hearts and minds of Nigerians towards the U.S. and away from Communism following independence. Simone, a fierce critic of the United States who ultimately renounced America and lived abroad, died not knowing she had been duped. (I just discovered Wind of Change, a podcast series that covers the Simone incident in its quest to figure out if the CIA wrote the Scorpion song by the same name.)

Word on the Street and in the Stars

If the CIA used highbrow culture through art and music, it wasn’t afraid to use lowbrow culture, either. A fascinating weapon in the CIA’s psychological warfare toolbox is laid out by Thomas Rid in his description of Project LCCASSOCK. This operation was a little different from, and less fraught than, the coopting of American art and music, but to me, is another thread in the same line of thinking. It’s also highly entertaining.

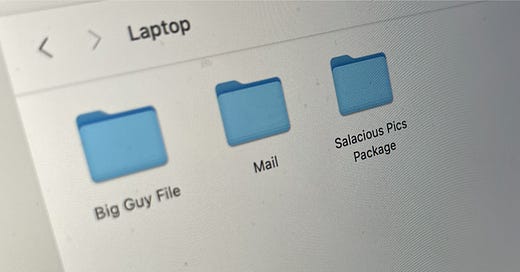

LCCASSOCK was the CIA’s largest “forgery factory,” producing “dummy issues” of East German magazines laced with disinformation that were read by ordinary people. But eventually Project LCCASSOCK began experimenting with its own original publications.

One of them, Rid notes, was a magazine called Klatsch, which means “gossip” in German (and an onomatopoeia of the sound of face-slapping). Klatsch appears to have been a Cold War version of the National Enquirer, consisting of made-up gossip and designed to be entertaining and memorable. It was also intended to subvert the attention of its target audience, for whom “trivia and gossip were alien to what was mainly a political and argumentative press landscape.” Rid recounts a few of the stories it ran:

The stories in Klatsch were wild. One, for example, claimed that Kruschev had accused Stalin of murdering his second wife. Another claimed that scientists were on the verge of discovering a gas that would divert the continental winds — and that the Soviet Communist Party’s 20th Congress had embraced the invention, hoping to prevent balloons containing print material from being swept across the border that divided the two Germanys.

The CIA’s project then extended to astrology. Rid observes that the “high popular demand for astrology was subdued in the East, where seeking truth in the stars was incompatible with ‘the precision of dialectic materialism.” (There’s that rigidity in thinking and worldview again.) The CIA sought to exploit this as a vulnerability; in addition to publishing an astrological magazine called Horizont, it targeted East German officials with “horoscope harassment letters.” Rid’s description of this operation cracked me up:

In early September 1957, just weeks before the U.S.S.R.’s launch of Sputnik, LCCASSOCK prepared a series of letters with personalized horoscopes for officials in the Ministry of State Security. The letters were mailed to pro-regime Berlin residents in the expectation that the collaborators would pass on the odd horoscopes to the actual targets in the MfS. Hans Truck, the new deputy head of the Stasi’s foreign intelligence arm, HVA, was targeted with eerie horoscopes predicting his doom. ‘These actions were designed to introduce a note of uncertainty within the MfS bureaucracy and, perhaps, to mislead MfS investigative energies,’ BOB reported back to Washington. The CIA base knew that the phony horoscopes were getting through to their MfS targets, but the results were unclear.

(Come on — you know they read the horoscopes and were freaked out just a little bit.)

The use of gossip and astrology was another way of subverting the minds of its targets. (LCCASSOCK also created a women’s fashion magazine and a very popular magazine about jazz.) Rid notes that “[t]he approach was tailored to Communist society, where individuals would have a hard time reconciling their past experiences and expectations with the harsh realities of everyday life — hence the temptation to escape from this reality into ‘superstition and fantasy.’”

The cultural Cold War is, as far as I’m aware, the closest we got to a true “Soviet style” active measures-type campaign, in the sense that it tried to really understand and exploit peculiarities in the Soviet mindset using weapons unique to America. So how should we evaluate these operations in retrospect?

Well for one thing, these operations were hard to measure in any concrete way. Rid notes, for example that LCCASSOCK became too costly to justify, and many superiors in the CIA didn’t really understand its “indirect approach” to combating Communism. Unlike CIA covert actions that had a clear outcome or single target, psychological operations directed at amorphous masses didn’t produce observable, tangible results. (LCCASSOCK was phased out and finally eliminated by 1961.)

There is also the issue of the harm inflicted on artists and musicians who were unwittingly coopted into the government program. As noted above, this was especially pronounced in the CIA’s covert operations involving Black jazz musicians. But Saunders also observes that when the CIA’s activities came to light, many modern artists — particularly those from foreign countries — felt “tainted” by even a tangential association with the agency. There is also the question of whether the CIA’s invisible hand distorted the “marketplace of ideas,” artificially inflating the value and importance of modern art (at least in elite and artistic circles) through its financial support and backing. There is no evidence that the CIA ever collaborated directly with artists to influence their expression, but it’s hard to know how their art may have fared if they had not had its indirect support.

On the other hand, it’s a testament to ideological tolerance that (at least a few) intelligence officials saw value in forms of unique American cultural expression, even when the people producing it, or their politics, were marginalized by the mainstream political establishment. It’s hard for me to imagine the KGB (or Putin), for example, channelling and promoting the work of individuals ideologically opposed to them; in comparison, these American operations seem weirdly, and paradoxically, quintessentially democratic. It’s also hard to object too much to the the CIA’s cultural weapons when juxtaposed with some of the more morally reprehensible and violent activities the CIA was involved in, like propping up dictators after coups, training paramilitaries, and attempting assassinations. In the end, subsidizing and promoting art and music — which we and the rest of society can still enjoy and benefit from today — seems pretty benign in the large scheme of things.

I’m not sure there are right or wrong answers here, and the questions circle back to some of the same ones raised by my lecture about the role of propaganda in a democracy generally. Saunders sums it up well in her book: “Here again was that sublime paradox of the American strategy in the Cold War: in order to promote and acceptance of art produced in (and vaunted as the expression of) democracy, the democratic process itself had to be circumvented.”

Audio Here:

Discussion Questions

What is it about art and music that makes its psychological impact different than, say, a book or political manifesto? Are they useful tools to have an in arsenal to counter foreign influence?

What are the ethics of using culture as psychological warfare? Does it matter if it is overt or covert, or does any promotion of artistic expression for political purposes a distortion of democracy and the marketplace of ideas?

Last week I asked you to think about how to frame today’s “battle” (most popular answer was ‘democracy v. authoritarianism’): Does America have any unique forms of cultural expression that could be channeled in this battle in the same way as during the Cold War?

Quick "war story.." Arriving south of Da Nang in 1965, our unit camped at the base of huge, cavernous rock monoliths, "Marble Mountain." At that early point in the war, the Viet Cong "owned" Marble Mountain and repeatedly sniped at us from honeycombed cave openings, day & night. One night, after about two weeks, we hung up a large canvas on the side of a six-by truck and our "film entertainment crew" turned on the big projector and we watched Jane Fonda in "Cat Ballou." By happenstance, I think, the"screen"was available to those perched with weapons way up above us, on Marble Mountain. The whole time the movie was on, they never fired at us. When it went off, they began firing again! The next day, we moved up on the monoliths and chased them out. No more Cat Ballou for them. But here is the point: We all--Viet Cong and Marines--wanted to watch Jane Fonda.

Question 1, the arts can speak straight to our hearts and minds without necessarily involving the "slow thinking" part of our cognition. We understand the emotions that the arts evoke without having to appreciate their logic and structure. They are a straight path to feelings.