Much attention has been paid to Florida, where in July 2022 Governor Ron DeSantis signed into law the “Stop W.O.K.E. Act” (H.B. 7) which, among other things, “revis[ed] requirements for required instruction on the history of African Americans” — a change that has caused confusion among educators and resulted in the reported removal of over 170 books from school shelves, including those about historical figures like Rosa Parks.

But if you haven’t been paying close attention, Florida isn’t alone, and it’s not just happening in red states: Since January 2021, forty-four states have introduced bills that would restrict how teachers in K-12 schools can educate students on issues of racism and sexism, and eighteen states have enacted these restrictions through legislation. Education Week has the following helpful map, as well as a more detailed table of the specific legislation proposed or passed in each state (I’ll be honest: I was surprised to see that a bill was introduced in Connecticut this year):

So how did we get here and why is this happening?

I think there are two answers, both of which require traveling back in time a bit.

“The Perfect Villain”

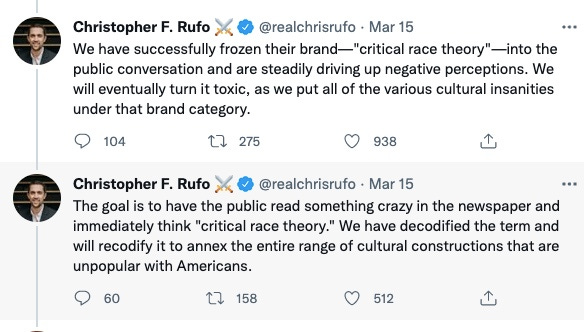

For the first, we only have to go back three years, to the start of the pandemic. That’s when a documentary journalist-turned-conservative activist, Christopher Rufo, began reporting on the anti-racism seminars the city of Seattle mandated for its employees. This excellent New Yorker article chronicles how, after publishing his article, Rufo began receiving “leaks” from other diversity trainings across the country (the pandemic made this easier, since these trainings were conducted online). In researching the common threads in these trainings, Rufo came across — you guessed it — citations to academic literature on CRITICAL RACE THEORY…and an information warrior was born. As Benjamin Wallace-Wells writes in the article:

As Rufo eventually came to see it, conservatives engaged in the culture war had been fighting against the same progressive racial ideology since late in the Obama years, without ever being able to describe it effectively. ‘We’ve needed new language for these issues,’ Rufo told me, when I first wrote to him, late in May…. ‘Critical race theory’ is the perfect villain, Rufo wrote.

He thought that the phrase was a better description of what conservatives were opposing, but it also seemed like a promising political weapon. ‘Its connotations are all negative to most middle-class Americans, including racial minorities, who see the world as ‘creative’ rather than ‘critical,’ ‘individual’ rather than ‘racial,’ ‘practical’ rather than ‘theoretical.’ Strung together, the phrase ‘critical race theory’ connotes hostile, academic, divisive, race-obsessed, poisonous, elitist, anti-American.’ Most perfect of all, Rufo continued, critical race theory is not ‘an externally applied pejorative.’ Instead, ‘it’s the label the critical race theorists chose themselves.’

Readers who are taking my Substack class and read my lecture on reflexive control will especially appreciate the significance — and frankly genius — of that last line. Using the name scholars have given to this area of research to frame the debate baits Rufo’s opponents into arguing about what CRT is and isn’t, which of course keeps the exact three words he wants (and their attendant connotations) in circulation.

Now, I’ve attended some pretty bad diversity trainings, and I don’t doubt that some of them use some questionable pedagogical ideas and methods. But there seems to me to be a big gulf between bias training for adult employees and standard school curricula that teach basic historical facts like the reason for the Rosa Parks bus boycott. The brilliance of the “critical race theory” framing is that it collapses any distinction between the two — the phrase is not only no longer tethered to its scholarly roots, it is basically applied to any topic that touches on discrimination or race and might make a white person feel discomfort.

The irony is that the entire premise of CRT — an area of legal scholarship that argues that racial biases are “baked into” laws and policies (like, say disparate sentencing laws for crack vs. powdered cocaine, or zoning ordinances that place liquor and adult stores near particular neighborhoods) — actually takes individuals off the hook for being personally racist. (Also FWIW, I went to one of the most liberal law schools in the country and they never hired a CRT scholar while I was there, despite student demands to do so…which gives you an idea of how sparsely this approach is actually “taught” in reality.) But there I go again, falling into the CRT definitional trap Rufo has set.

If we break out of the “what is CRT?” debate and zoom out, we can see a bigger picture come into focus. Kimberlé Crenshaw, a law professor at Columbia and UCLA and the person who coined the term “critical race theory,” sees a connection between the increased attention to racial issues following the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and the “anti-woke” agenda. The New Yorker piece describes her view:

Crenshaw sounded slightly exasperated by how much coverage focussed on the semantic question of what critical race theory meant rather than the political one about the nature of the campaign against it…. ‘Reform itself creates its own backlash, which reconstitutes the problem in the first place,’ Crenshaw said, noting that she’d made this argument in her first law-review article, in 1988. George Floyd’s murder had led to ‘so many corporations and opinion-shaping institutions making statements about structural racism’—creating a new, broader anti-racist alignment, or at least the potential for one. ‘This is a post-George Floyd backlash,’ Crenshaw said. ‘The reason why we’re having this conversation is that the line of scrimmage has moved.’

In other words, the raised public consciousness of how racism affects certain groups — particularly a greater awareness and concern among many whites who may not have understood or acknowledged it in the same way before — spurred reforms attempting to address this inequality (even if it sometimes took the form of poorly designed corporate trainings). This was a threat to existing power hierarchies, which in turn resulted in backlash that requires denying that that the power hierarchies exist in the first place. (In a way you could say that the freak out over CRT proves the whole premise of CRT.)

But the cycle of reform, backlash, and historical whitewash didn’t start with George Floyd: It has a long history, and for that we have to go back another one hundred and twenty years.

“Mission Accomplished”

One of my favorite books that I read before the pandemic was Ethan Kytle and Blain Robert’s Denmark Vesey’s Garden: Slavery and Memory in the Capital of the Confederacy. Kytle and Roberts use the city of Charleston, South Carolina as both an epicenter and microcosm of the memorialization of two divergent narratives about slavery after the Civil War. On the one hand, white Southerners, reeling from the humiliation of defeat of the Confederacy, sought to both deny the centrality of slavery in the war and soften its role in the region’s past, either by distancing themselves from the it (e.g., claiming that it was an institution involuntarily imposed on the South by Britain and the North) and/or by romanticizing it (e.g., claiming that it wasn’t that bad for Blacks and that they benefited from it as well): This “Lost Cause” narrative became institutionalized in various forms in the South through the twentieth century. On the other hand, the realities of the brutality of slavery were passed on to future generations of Blacks through oral history, public rituals, and musical traditions. These two versions of history still compete with each other today.

The authors’ thesis is that America’s failure to confront this bifurcated history — and in particular, to incorporate the reality of the lived experience of slavery and its legacy into our common understanding of this country’s past — is what continues to keep us divided, and stuck, on issues of race.

I found myself going back to this book as the CRT controversy began to pick up speed during COVID, because the whole movement sounded eerily familiar. Indeed, Kytle and Roberts address how at the turn of the twentieth century, the white South realized that children who were being born into a post-slavery era (and to parents who had no direct knowledge of slavery) might be exposed to unflattering facts about the South. To combat this, the Lost Cause narrative would have to be integrated into school curricula: “Education, in short, became a chief front in the memory battle over the next three decades.”

The head of the movement to revamp southern education was Mary B. Poppenheim, president-general of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and publisher of the women’s journal Keystone. She was basically the Christopher Rufo of the Jim Crow era, or maybe Rufo is Poppenheim reincarnated. Either way, I wish I could just link to the entire section in the book about her, because the parallels to her crusade and the phenomenon happening now are incredible. Here is an example:

In 1904, Poppenheim reported on a new state initiative to supplement what South Carolina children learned about the Civil War in school by organizing auxiliary youth chapters under the guidance of local parent chapters. As older southerners passed away, the UDC had to ensure that the next generation was armed with a proper understanding of the conflict….

Poppenheim and her UDC colleagues kept a careful watch of the textbooks used in the state’s public schools as well. In early 1905, the Historical Committee sent every chapter in the state a circular that covered a number of topics, including the textbook in question. In addition, the Keystone identified appropriate textbooks and histories as well as books that the UCV [United Confederate Veterans] viewed as biased against the South.

At the annual meeting of the South Carolina division of the UDC, held in Camden in 1903, Poppenheim focused the Daughters’ attention on one objectionable text in particular: Edward Eggleston’s A History of the United States and Its People. Assigned in numerous southern schools, including those in Charleston, Eggelston’s textbook held that slavery caused the Civil War. In the years that followed, Mary, her sister Louisa, and other UDC members led a crusade to remove Eggleston’s book, and other unfair histories, from South Carolina classrooms. The Historical Committee circulated lists of acceptable and troubling books to all UDC chapters, and members pressured local school districts and principals to adhere to them.

By 1914, the authors write, Poppenheim had declared “mission accomplished,” stating at a UDC conference that the the previously “poisoned” schools were now “pure.”

We have of course seen the thru-line from this educational “reform” to contemporary events, like the 2017 Neo Nazi march in Charlottesville over the removal of Confederate statues (Kytle and Roberts note that the UDC was largely responsible for erecting those, as well). In its most extreme form, we have seen it in the murderous rampage of Dylan Roof at Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston in 2015 — Kytle and Roberts observe that Roof targeted the church because he believed that Blacks were using exaggerated myths about slavery to justify a takeover of the United States. (He had visited Charleston six times before the shooting, visiting plantations and other slave sites.)

But to me, the tension between these competing historical narratives was perfectly encapsulated by an incident in 2021, when the organizers of an American Legion-sponsored Memorial Day service in Hudson, Ohio, cut the mic of retired Lt. Col. Barnard Kempter after he began explaining how the holiday has its origins in a ceremony commemorating fallen Union soldiers started by freed Blacks in Charleston after the Civil War:

The organizers of the event, Cindy Suchan and Jim Garrison, admitted that they cut off Kempter’s mic because it “was not relevant to [their] program for the day,” since “the theme was honoring Hudson’s veterans.” (NOTE: Following an investigation by the American Legion, which found the actions of the organizers “premeditated,” both Suchan and Garrison were forced to resign their positions and the charter of the Hudson American Legion post was suspended.)

In case you’re wondering what got cut from the speech (a full draft of which you can read here), it was before he could say the following:

More importantly than whether Charleston’s Decoration Day was the first, is the attention Charleston’s Black community paid to the nearly 260 Union troops who died at the site. For two weeks prior to the ceremony, former slaves and Black workmen exhumed the soldiers’ remains from a hastily dug mass grave behind the racetrack’s grandstand and gave each soldier a proper burial. They also constructed a fence to protect the site with an archway at the entrance that read ‘Martyrs of the Race Course.’

The dead prisoners of war at the racetrack must have seemed especially worthy of honor to the former slaves. Just as the former slaves had, the dead prisoners had suffered imprisonment and mistreatment while held captive by white southerners.

Not surprisingly, many white southerners who had supported the Confederacy, including a large swath of white Charlestonians, did not feel compelled to spend a day decorating the graves of their former enemies. It was often the African American southerners who perpetuated the holiday in the years immediately following the Civil War.

African Americans across the South clearly helped shape the ceremony in its early years. Without African Americans, the ceremonies would have had far fewer in attendance in many areas, thus making the holiday less significant.

My generation grew up listening to the famous radio personality Paul Harvey. Paul would say at the end of his broadcast, "And now you know the rest of the story." And now you know the rest of the story about the origin of Memorial Day.

Imagine: The organizers could not stand for the audience to even hear this history. I have to say that it’s a little weird that this particular censorship took place in Ohio, considering that the state fought for the Union — but that only underscores how we are still fighting an information war over the same exact subjects. In fact, Kytle and Roberts’ account describes the precise history Kempter sought to acknowledge and revive in 2021, which was already being erased, and replaced, by the late nineteenth century:

Knowledge of the Martyrs of the Race Course ceremony, to be fair, had faded fast in many places. After Ladies’ Memorial Associations across the South flocked to Confederate graves in 1866, northern newspapers reminded their readers that this custom was initiated by James Redpath and the black citizens of Charleston. But by 1868, when the Grand Army of the Republic called for its members to honor the federal dead in an annual May ceremony, numerous observers insisted that the northern veterans organization was trying to usurp a tradition begun by white southern women. The debate over the origins of Decoration Day lingered for decades.

Perhaps to solidify their version of history, in 1903 white Charlestonians renamed the Washington Race Course for Wade Hampton, a Confederate colonel, governor of South Carolina, and fierce defender of slavery. In the words of Kytle and Roberts, “The site of a black-built tribute to the loyalty of Union soldiers in 1865, the old racetrack became the symbolic home of loyalty to white supremacy.”

Past is Present

If we look at the CRT controversy against this larger historical context, it becomes clear that the current reform in education isn’t about CRT — it’s a battle over our collective memory. CRT just provides a convenient way for Rufo and state legislatures to pick up the baton and continue the work Poppenheim started over a century ago.

There is one big difference: There’s way more history now! After all, the entire institution of Jim Crow of which Poppenheim was a part recreated the underlying racial hierarchies of slavery — it “reconstituted the problem,” to use Crenshaw’s phrase. So that has to be glossed over, too, along with all of the backlashes that followed, reconstituting the problem again and again.

I could take another thousand words to explain this in more detail, but I’m not sure I can do better than this brilliant and powerful two-minute whiteboard explanation by

:Mind blown, right? It doesn’t get clearer than that.

I’ll conclude by saying that I love America. And I don’t hate white people, or think they are all racist. In fact, learning about the worst parts of our history, and our collective resilience in the face of them, make me feel like this country has the capacity and potential to live up to its Founders’ promise. We can debate how we should best confront and teach this complicated past to our kids. But what shouldn’t be up for debate is whether to teach it at all.

When I learned about slavery, Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement (granted these were whitewashed versions), I didn’t become ashamed to be white. I thought, “Oh wow--white people in power can do some really heinous things.” I don’t know what percentage of history deniers think THAT’s what children have to be “protected” from, but it’s not zero.

On a recent visit to Charleston we retained a guide to show us the city. He never showed us nor mentioned the old slave market building which is now a museum. He never showed us the site from which Robert Smalls took over a confederate ship and sailed it, along with 16 other slaves, to the Union stronghold of Fort Sumter. Even in the otherwise liberal city of Charleston,the myth of the Lost Cause still exists for some of it’s citizens.