Your Cheat Sheet on Complicity in the Epstein Saga

Who knew complicity could be so...complicated?

One thing I’ve learned as I’ve been researching my book on complicity and moral courage is that everyone has a theory. “So-and-so is totally complicit in X!” they’ll exclaim, or “Anyone who does Y is complicit in Z.” Intuitively it feels like that should be true, but…it turns out that complicity is not that simple.

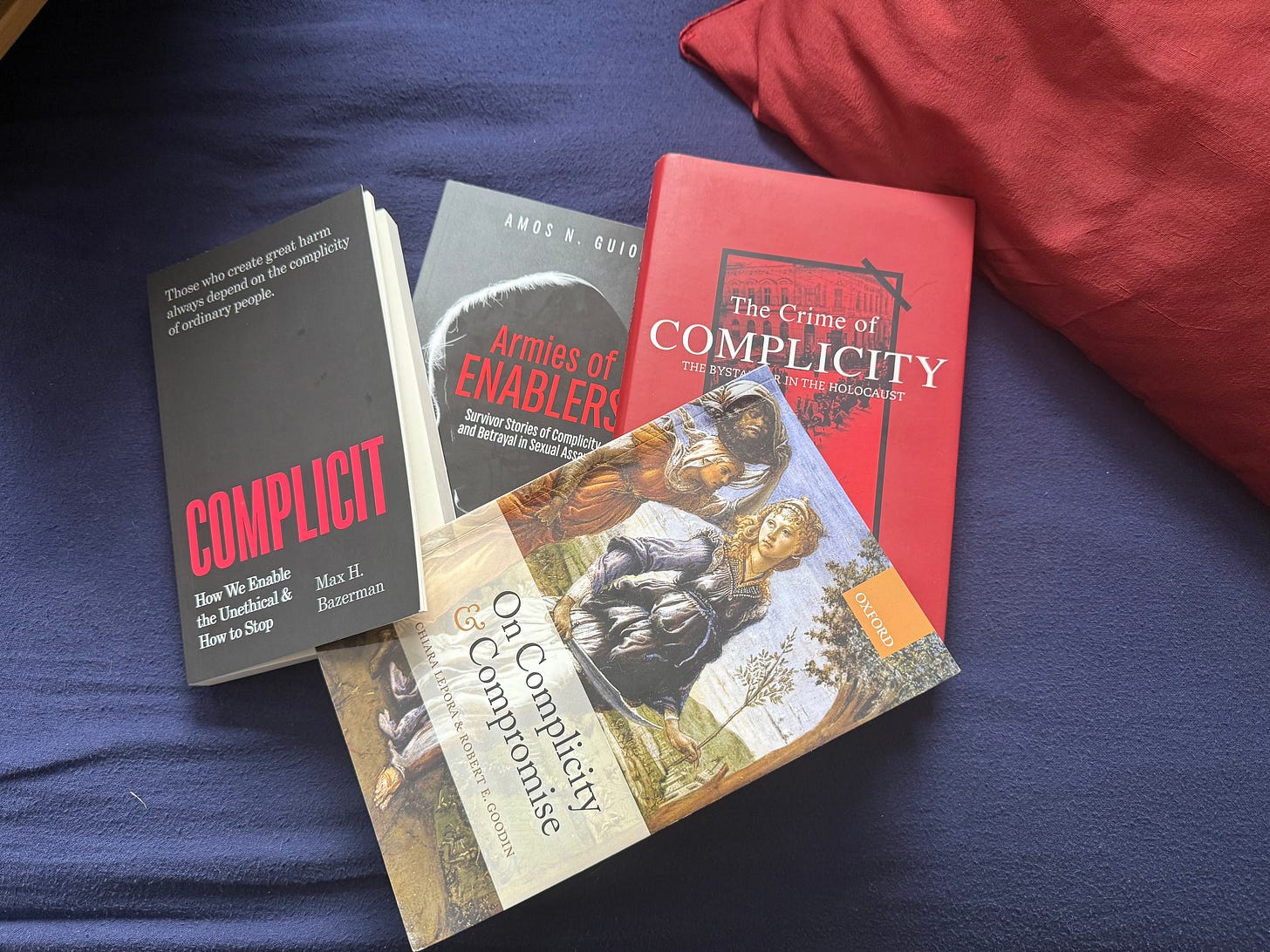

First things first: What does it mean to be “complicit”? There is, in fact, a whole disquisition on the subject, On Complicity & Compromise by Chiara Lepora and Robert E. Goodin (shown in the picture above). It’s dry, but fascinating, and I’ll break it down for you. Complicity — made up of the root cum (together with) and plico (to enwrap/fold together/entwine) — is in its most literal meaning about not acting alone, but being folded into or entangled with something or someone else. The authors of the book define it as “committing an act that potentially contributes to the wrongdoing of others in some causal way.”

I think often people conflate complicity with something that is morally or ethically fraught, generally speaking — for example, “If I buy stock in Tesla, am I complicit in the dismantling of USAID?” or “If I use Amazon, am I complicit in the undermining of the free press?” I would argue: No. That’s not to say there aren’t moral questions you’d want to ask yourself before you add to any narcissistic billionaire’s coffers, or that you wouldn’t have strong ethical grounds for refusing to invest or use their products or services. But it wouldn’t make you complicit in their actions because the causal link to the ultimate bad conduct is too tenuous: Lepora and Goodin argue that the contributory behavior has to be “definitely essential” or “potentially essential” to the wrongdoing.

I know some people will feel like this definition is too narrow and lets too many people off the hook. I say it does the opposite. If EVERYONE is complicit in EVERYTHING, then you’re deflecting the focus from the people who are actually responsible. I mean, if all of us who pay U.S. taxes are “complicit” in the kidnapping of Nicolas Maduro, why bother examining the actual role of the people who made the decisions? It’s just a slippery slope.

Importantly, there are some other nuances that matter that don’t let people off the hook. For instance, you don’t need to share the goal or purpose of the principal in order to be complicit. As long as you are aware that the principal’s plan or actions or wrong and your actions are voluntary, you can be complicit even if you disapprove of the action or you contribute reluctantly. And, in some instances, you can be complicit by not acting at all. Bystanders who witness a crime or wrongdoing and have the power to impede or stop it but don’t, can be complicit in the act and the harm that results — at least in the moral, if not legal, sense. (Professor Amos Guiora, author of The Crime of Complicity: The Bystander in the Holocaust, makes a compelling case for why bystander inaction should be a crime.)

So what does this mean for the Epstein case? Well, Lepora and Goodin argue that complicity can be defined along a sliding scale. At one end are “co-principals,” or people who act in unison. At other end are “non contributors,” or people whose actions are not causally connected OR had no way of knowing what they were doing contributed to the wrongdoing of others. Most criminal laws are focused mainly on the first category (and even there, it is pretty narrow, as you will see below). The gray area is when people are acting with knowledge of the wrongdoing, but either don’t share the co-principal’s purpose or aren’t actively participating in it .

Lepora and Goodin’s rule of thumb is this: “An act of complicity will be worse the more central, proximate, or irreversible it is with respect to the principal wrongdoing.”

I’ll break down the sliding scale, and who belongs in each category, below (I’ve included their etymology for each type of complicity because it helps convey why these actions are so pernicious):1

The Co-Principals:

This is where our attention is usually focused, because this is where the crosshairs of criminal prosecution usually land. However, as you will see in the categories below — which are discussing complicity in the moral and definitional, not legal sense — criminal law is very narrow when it comes to complicity and is unlikely to capture even all of the co-principals in its net.

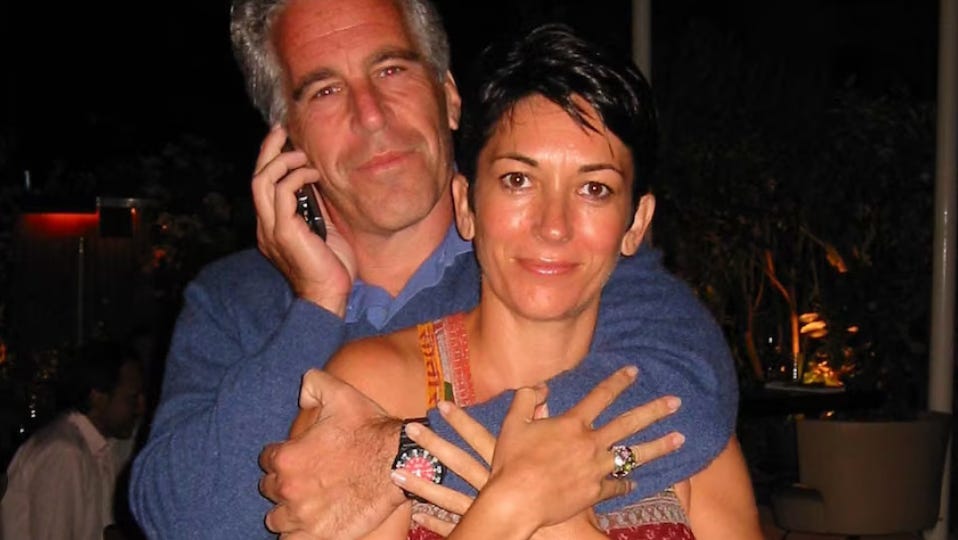

Full Joint Wrongdoing

OK. So I hope I don’t need to spend a lot of time in this category. These are the criminal ringleaders, in which each person agrees and participates fully. Obviously in the Epstein case, that’s Epstein himself and Ghislaine Maxwell. (That the Justice Department has even tried to muddy the waters on this front is still bonkers to me.)

Conspiracy (cum + spire — “to breathe”): breathing life into a plan

Conspiracy as a form of complicity is an agreement to a plan to commit wrongdoing. Here’s where we see the first departure in the law: the crime of conspiracy requires both an agreement to commit a crime (i.e., not just do something bad or unethical), but also an “overt act” in furtherance of that agreement.

I think it would be fair to characterize anyone to whom Epstein’s victims were trafficked as being complicit with Epstein as moral co-conspirators, and potentially legally liable as well. Epstein survivor Virginia Guifree alleged that she was trafficked to Andrew Mountbatten Windsor, and recent files reveal emails from him to Maxwell asking, “Have you found me some new inappropriate friends?”

Of course, he’s not the only one: It’s clear that part of what is being concealed in the stonewalling of the files’ release are others who were similarly involved in Epstein’s lurid activities: one Justice Department memorandum actually references ten potential co-conspirators who have not yet been identified.

Cooperation (cum + operare — “to ensure the functioning”): acting interdependently towards a common goal

Cooperators are different from conspirators in that they are not involved with the planning of the wrongdoing itself. However, they readily adopt the plan after-the-fact and orient their behavior around it.

In this group I place Epstein’s lawyers who helped him get his “sweetheart deal” from the U.S. Attorney’s office in Miami (more on that below), including Kenneth Starr and Alan Dershowitz. I paused to consider whether it would be wrong to suggest that lawyers providing a legal defense are complicit in the wrongdoing itself, but given the secrecy of the deal Epstein got and the fact that it allowed him to continue his trafficking and abuse, I’m OK with it in this case.

Normally it is harder to be complicit in an action after it has happened. But if we are including as part of the wrongdoing the ongoing harm to victims created by the protection of people involved with Epstein, then Pam Bondi, Todd Blanche, Kash Patel, and Mike Johnson (and every other member of Congress who tried to stop the release of the files) are Cooperators, as well.

Collusion (ludere — “to play”): acting in secret concert with

Ahhhh, collusion. That lovely word we came to know and hate in Trump 1.0 and that was the legal equivalent of Jell-o.

Collusion means cooperation in secret for the mutual benefit of the colluding parties at the expense of unwitting third parties. In the legal realm, we see this in limited arenas: price fixing by companies is a form of collusion. So are things like insider trading or point shaving in sports. But outside of these specific contexts, collusion is not a crime, unless it meets the bar for conspiracy.

It’s still shady as hell and a form of complicity. Here I have given the award to Alex Acosta, the former U.S. Attorney for Miami and architect of the 2008 “deal of the century” that let Epstein off the hook for another decade plus. According to the OIG’s report on Acosta’s handling of the Epstein case, he secretly met off-site with Epstein’s lawyers (Starr and Dershowitz), asked the FBI to stand down on further investigation (without explaining why), hammered out a deal that protected not only Epstein but co-conspirators both “known and unknown” to the U.S. Attorney’s office, and then sealed the deal without consulting the victims, in violation of the Child Victim Rights Act.

I would also include in this category the banks and other financial channels that facilitated Epstein’s trafficking network, which clearly operated in secret or without triggering the kind of scrutiny they should have.

The Contributors:

Here’s where we get to the really fascinating, albeit legally unsatisfying, part of the spectrum. The suite of actions below largely do not constitute “wrongdoing” in the criminal sense. Yet they encompass behavior implicated by a huge swath of people mentioned in the Epstein files. Contributors are less directly causally connected to the wrongdoing, but can contribute to the wrongdoing by facilitating, legitimizing, or incentivizing the principal’s actions. “[A]ll that is necessary,” Lepora and Goodin write, “is that the complicit agent ‘knows, or should have known, that by [so acting] he or she will advance whatever intentions the principal has.’”2

Precisely because these behaviors are not going to ever be adjudicated in a court of law, I think it’s important to be able to name them specifically:

Collaboration (cum + laborare — “to work”): following the leader

Collaboration is where things start getting a little tricky. Collaborators do not participate in the planning of the wrongdoing, nor do they necessarily adopt the plan as their own, like Cooperators do. However, Collaborators contribute to the operationalization of the plan. From a criminal law perspective, this might fall into the realm of accomplice liability, like aiding and abetting — though it could be causally tenuous enough to not even meet that threshold.

I put the Palm Beach Police Department here because they were the ones who caved to Epstein and let him walk out of the jail for 12 hours of the day during his one year in “jail.” I also think of people this category as the “logistics” of Epstein’s operation — the pilot who flew Epstein and his buddies, with obviously underage girls, to and from his island. Perhaps the people who worked at the island, or even at Epstein’s mansion. Maybe Acosta’s underlings at the Justice Department who were told to help put together his sweetheart deal.

Technically speaking, I think collaboration could also include victims who Epstein and Maxwell conscripted into becoming recruiters for new victims. It’s important to note that from a criminal law perspectives, they would likely be considered “co-conspirators.” In fact, the line AUSA in Miami told OIG investigators that she did not see the clause immunizing co-conspirators in Epstein’s non-prosecution agreement as a red flag because the people that had been identified as co-conspirators to that point were also victims (this is an area where legal responsibility departs from moral responsibility). For this reason, it’s also possible that victims comprise one or more of the ten co-conspirators referenced in the released files. The point here is that where a shared purpose might be absent, you can see how the responsibility for complicity can get murky.

Conniving (cum + nivere —“to wink at, to nod with the eyes, to twinkle the eyelids, to shut the eyes”): ignoring or tacitly assenting to the wrongdoing

Here we begin to enter the forms of complicity that typically do not have a causal relationship to the central wrongdoing. Connivance is the closest to the proverbial “bystander” because someone who connives neither participates in the planning nor adopts the plan as their own. Rather, Lepora and Goodin write, “[t]hey merely stand aside to let others act on it.” Here is where inaction can qualify as complicity. The test is the following: “If there was something you could have done to stop it and you didn’t, your inaction can properly be counted as part of the causal chain that allowed the event to occur.”

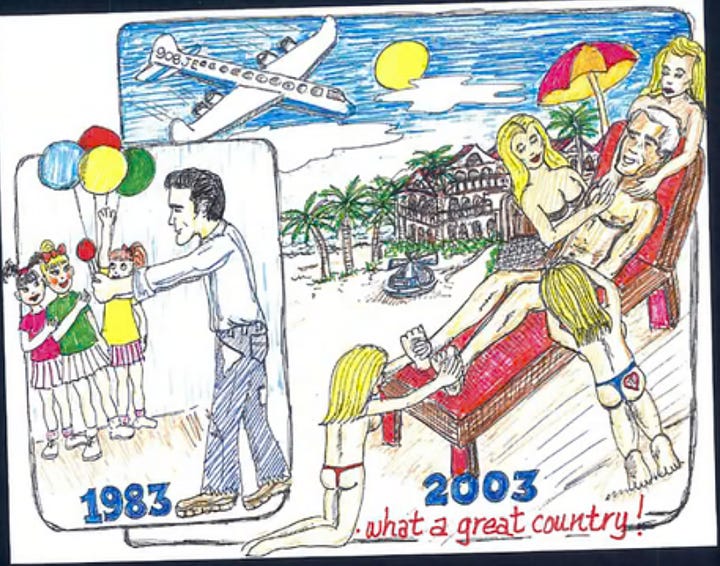

The revelations of Trump’s awareness of Maxwell’s activities at Mar-a-Lago, particularly her recruitment of girls from the spa to work at Epstein’s mansion, strikes me as a clear example of connivance. Trump’s own admission that Epstein “stole” women from Mar-a-Lago is an confession that he was aware of the pipeline from his resort to Epstein.

Connivance, Lepora and Goodin write, can also constitute complicity in situations

where people are involved in some recurring pattern of social interaction. There, the same situations recur, time and again, involving the same agents. Then your acts of connivance today may contribute causally to the wrongdoer’s repeating the wrong on the next occasion. It does so by making the wrongdoer confident, on the basis of previous experience, that again in the future onlookers will connive rather than intervening to stop the wrong when they see it occurring.

Hmmm. This is where Trump’s obviously close social relationship with Epstein and visits to his home — where Epstein had lewd photos on display and sometimes even girls he abused present — would (at the very least) constitute connivance.

Condoning (cum + donare — “to donate, to bestow, to give”): direct acknowledgment of the wrongdoing and explicit pardon of it

Condoning wrongdoing involves approving of it, and in doing so, forgiving it. When it comes to Epstein’s activities, condoning can say a lot of about character, but does not necessarily imply complicity: For instance, if there is some random pedo in Montana who reads about Epstein and thinks what he did is just fantastic, that is “condoning,” but at the most it shows that the person condoning it is morally bankrupt and potentially evil, but not complicit in Epstein’s criminality.

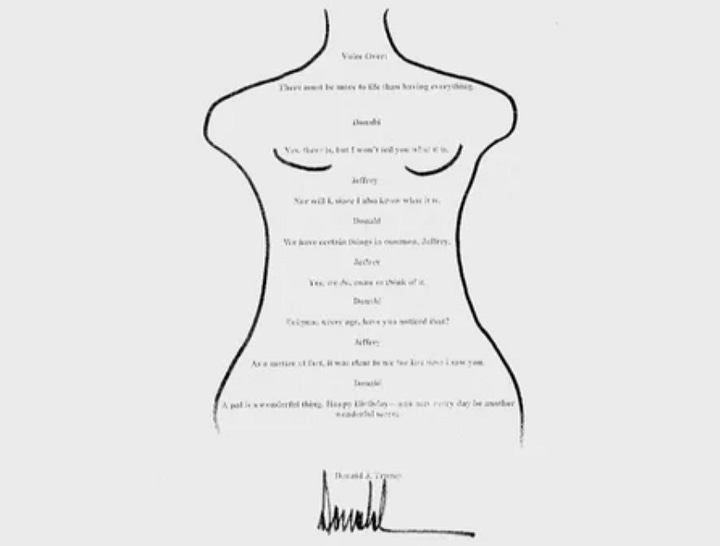

The calculus changes, though, is the person or people condoning the action signal an awareness and approval of the wrongdoing, and in doing so, encourage the principal(s) to continue (or at least feel that they won’t be sanctioned for doing so). This is where proximity matters, particularly with Epstein’s social circle. I would say that almost every person who signed Epstein’s “birthday book” — most of whom it seems, had a pretty good idea of what was going on — fall into this category, as their contributions to his gift consistently condone his behavior.

Consorting (cum + sors — sharing the same fate): implication of intimacy

Oh, Larry. Larry, Larry, Larry. Who shall henceforth be known as Epstein’s “consort.”

Consorting — keeping company — with a principal contributes to the wrongdoing when their relationship “signals one’s agreement with and approval of their actions; and that encourages them in their wrongdoings.” Here is where the temporal relationship to the misconduct is important. What I mean is that it is possible that, prior to 2008, some people may have plausibly consorted with Epstein (particularly if they weren’t in his close social circle) and not known what he was doing. But after 2008, when he was literally convicted of a sex crime (the one he pleaded to in state court), consorting with Epstein is a deliberate choice. One that Larry Summers chose to make, up to a few days before he was arrested again in 2019. No doubt others did, as well — check the time stamp on communications released in the files.

Contiguity (cum + tanegere — touch together): close proximity, without actual contact

Contiguity is the least “causal” form of complicity — it is essentially mere affiliation with a principal wrongdoer, though not necessarily in a social or intimate way. A person or entity that is contiguous contributes if their association is interpreted as implicit approval and the secondary agent knew it could be interpreted that way.

Hello, M.I.T. Although some institutions, like Harvard, decided not to accept further gifts from Epstein after his 2008 state conviction, M.I.T.’s Media Lab continued to do so, even into 2019. M.I.T.’s president, L. Rafael Reif, acknowledged how this constituted complicity with Epstein’s wrongdoing, writing, “with hindsight, we recognize with shame and distress that we allowed MIT to contribute to the elevation of his reputation, which in turn served to distract from his horrifying acts.” At least he gets it.

One thing I noticed as I was linking to sources for this post is that almost all of them include the caveat, “So-and-so has not been accused of criminal wrongdoing.” I hope this post shows that this caveat misses the point, and is misleading — it suggests that someone is “innocent,” and therefore has no responsibility at all for Epstein’s actions. The criminal code is not the only yardstick we should be using to measure people’s behavior.

I think we’ve all been searching for the words to describe why, even if someone revealed in the Epstein files isn’t going to be prosecuted for a crime, they may still be morally responsible for being complicit. I hope this post offers the language to do that.

These categories and the etymology are drawn from Chiara Lepora and Robert E. Goodin, On Complicity & Compromise, (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Citing L. May, Genocide: A Normative Account (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 169.

Fantastic work, Asha! This should be required reading for the nine justices.

John Almond

Tucson

Excellent commentary, very informative.

After your third category I began thinking of it as working outward by level in Dante's "Inferno".